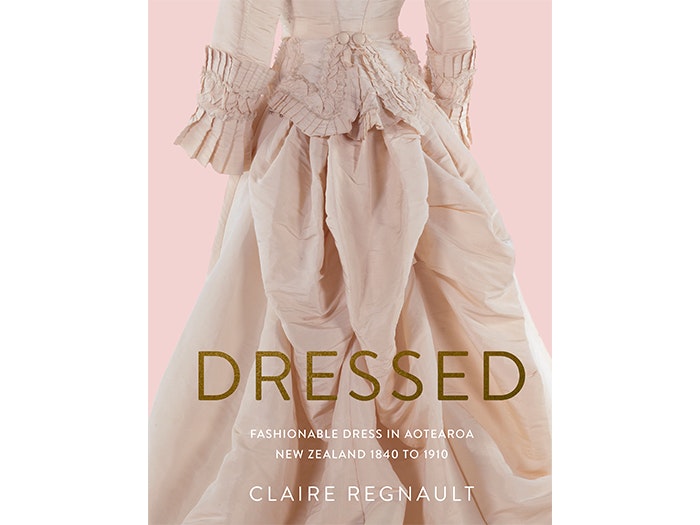

Q&A with Claire Regnault, author of Dressed

Claire Regnault discusses Dressed: fashionable dress in Aotearoa New Zealand 1840 to 1910 with Te Papa Press

Claire Regnault is Senior Curator New Zealand Culture and History at Te Papa and has worked as a curator in the art gallery and museum sector since 1994. Her curatorial practice is eclectic in nature and she is particularly passionate about New Zealand’s fashion history. She is the author of New Zealand Gown of the Year (2003), and co-author, with Douglas Lloyd Jenkins and Lucy Hammonds of The Dress Circle: New Zealand Fashion Design Since 1940 (2010), which was a finalist in the 2011 NZ Post Book Awards. She is an active member of the Costume & Textile Association of New Zealand, and regularly contributes to the association’s symposia and journal.

"Along the way certain objects would pop up – such as the Graham & Co. folding dress stand – which would inspire a new obsessive train of research, and the question ‘How can I work this in?" – Claire Regnault

Where did the idea for this book first come from?

In 2010, I published a book with Lucy Hammonds and Douglas Lloyd Jenkins called The Dress Circle, which focused on New Zealand’s fashion design history from 1940 to the mid-2000s - Dressed is a ‘prequel’! Around the time The Dress Circle was published, I got the job at Te Papa and suddenly had access to a wonderful dress collection. As I got to know the collection, I saw an opportunity to develop a book on nineteenth/early-twentieth century dress that was based around actual surviving garments.

Why did you want to write it?

There was a big gap in the literature. While there have been journal articles and chapters here and there looking at nineteenth century dress in Aotearoa, one of the last books published on the subject was In True Colonial Fashion: a lively look at what New Zealander’s Wore by Eve Ebbett in 1977. It needed an update!

Did the scope of the project change as you got deeper into your research?

Yes – originally, the framework was chronological like The Dress Circle, but I quickly realised that it would better to organise it thematically in order to avoid repetition. Most of the chapters began with one or two key garments that had caught my eye – such as Louisa Seddon’s ‘Coronation’ themed dress – which operated as a springboard into a theme. I tend to work pretty organically, and one dress would typically lead to another. The chapter on feathers in fashion was not originally in the plan at all, but the material was just too captivating to let go or squash into a paragraph or two, so a chapter it became. Along the way certain objects would pop up – such as the Graham & Co. folding dress stand – which would inspire a new obsessive train of research, and the question ‘How can I work this in?’

What can their clothing tell us about the people of the past in a way that their other possessions and the artefacts of their world does not?

Clothing reflects a person’s personal presentation to the world, and of course being worn on the body is very intimate. Many of the garments in the book were made specifically for the wearers. Clothing design was much more collaborative or participatory in the period covered by Dressed – women purchased fabric and trimmings themselves and either made their own clothes or discussed what they wanted with a dressmaker. As such, each dress is bespoke – made to an individual’s measurements, and sometimes including extras such as ‘bust improvers’ to compensate for perceived bodily ‘deficiencies’. Let out seams, mends, adaptations and even stains all provide information or prompt questions about a person and their life.

Is it a marvel that as much nineteenth century women’s fashion exists in our museums in Aotearoa as it does?

Not really, as thankfully people often treasure clothes for sentimental reasons as reminders of significant events and loved ones. However, this tendency does mean that collections primarily feature ‘special occasion’ clothing rather than that of the everyday, which got worn and worn, mended, refashioned and recycled. So collections are rather biased.

For this book you have concentrated almost exclusively on clothing that has a provenance, whose wearers were known. Why was this important?

I ideally wanted to focus on garments that either had a wearer and/or a maker attached to them. That meant I had a life to pursue and if I was lucky, such as in the case of Ellen Tripp (nee Harper) or Lavinia Coates, that I might be able to find some of their words and thoughts and feelings and get a little bit more of an insight into the person who once inhabited the garment. With Ellen, in particular, I was even able to find a quote about one of her garments held in the Canterbury Museum. I considered it a research trifecta when I was able to find a garment, a wearer and a photograph! Personal stories help bring life and context to the garments – without them they are simply examples of type.

This is a history of fashionable dress within a settler society, a colony of Britain. In what way does that history differ from a history that might be written about nineteenth century dress in another colony during that period, about Australia, for example?

As a localised history of dress, Dressed explores fashionable dress made and worn by Māori and Pākehā women living in this place. It takes place in our landscape with its particular challenges, our streets, shops and ballrooms, and is populated by names that will be familiar with many New Zealand readers.

At well over 400 pages this book has been clearly quite an undertaking. The amount of photography alone is significant. Tell us a bit about that.

The photography element was huge, and is a reason I think, why there are not many publications on early dress in New Zealand. It takes a lot of work and expertise to mount an historical garment – it’s not simply a matter of slipping the garment from its box over the shoulders of a ready-made dress form – their shoulders are too broad, their waist and busts often too big.

Because of their age and delicacy, many of the garments, required conservation treatment before mounting. Some garments just needed a bit of refreshing following years of being in storage or a bit of humidity treatment to relax creases and fringing etc. Other garments needed to be stabilised before they could be mounted: shattered linings encased, stressed waistbands supported and so on. This work was carried out by our amazing team of textile conservators – Kate Blair, Rachael Collinge and Rangi Te Kanawa.

Once the conservation treatment was completed, Sam Gatley, who specialises in mounting historical garments, created bespoke forms for each dress. Sam started with a small form of her own making with fashionable nineteenth century sloping shoulders and then padded the form – particularly the shoulders and breasts – to the shape of the dress; quite an intimate process. She also created underpinnings to support the shape of the skirt, including a crinoline, bustle and petticoats. For the Busvine riding habit she even sculpted removable legs so that we could showcase the breeches.

It’s great to see so many garments from other museums around Aotearoa. How did all that come about?

Collection envy! At Te Papa we have a good collection, but we certainly don’t have examples of everything I wanted to include. The first museum I made a research visit to was the Canterbury Museum as I knew that they had a couple of spectacular, provenanced fancy dress costumes. The chapter on balls started out solely as a chapter on fancy dress as that was one of my original obsessions. I also wanted to incorporate stories of people, communities and businesses from around New Zealand, and these are often best represented by regional museums.

Favourite dress, and why?

My favourite changes constantly … it’s often more details than actual whole dresses, such as an origami trim on a plaid dress with pagoda sleeves, the figurative lace from one Louisa Seddon’s dresses, and the sprig-print lining of a J Ballantyne & Co. bodice.

You might also like

Dressed: Fashionable dress in Aotearoa New Zealand 1840 to 1910

When crinolines, bustles and ostrich feathers were the height of colonial fashion – from ball gowns and riding habits to tea gowns and dresses worn for presentation to Queen Victoria.

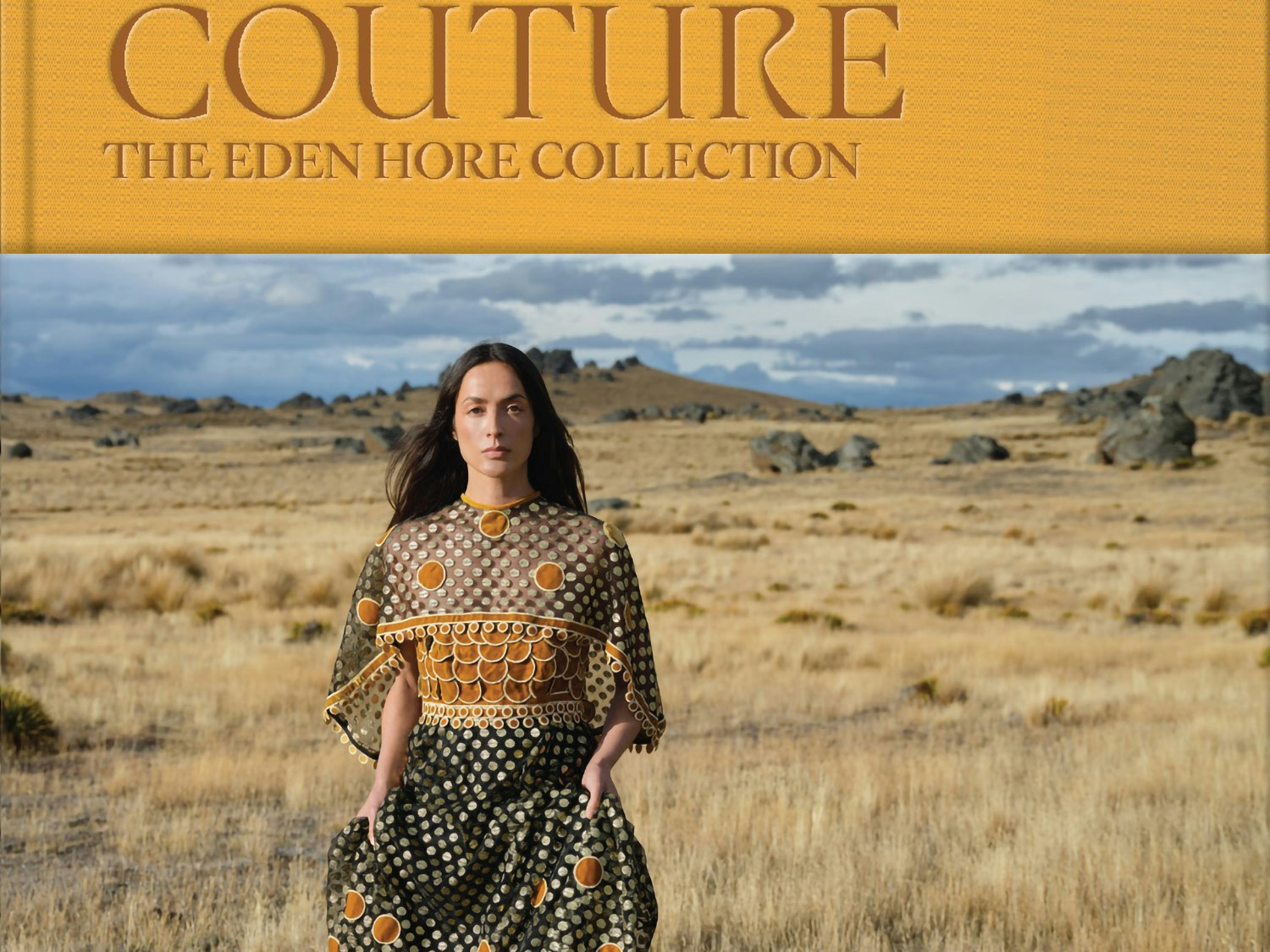

Central Otago Couture: The Eden Hore Collection

A fascinating record of high-end New Zealand fashion and an enigmatic collector.