Crafting Aotearoa: A Cultural History of Making in New Zealand and the Wider Moana Oceania

A landmark publication that takes another look at craft and its broader cultural role.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Karl Chitham, Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai and Damian Skinner discuss Crafting Aotearoa with Te Papa Press

Kolokesa U Māhina-Tuai has a background in art history, social anthropology and museum and heritage studies and was curator of Moana Oceania cultures at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa from 2004 to 2008 and Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira from 2013 to 2017. She has been a guest curator and consultant for Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, and a consultant for Alt Group and the Government of Tonga’s Culture Division, Ministry of Tourism. She is co-author of Nimamea‘a: The fine arts of Tongan embroidery and crochet (Objectspace 2011), Tangata o le Moana: New Zealand and the people of the Pacific (Te Papa Press, 2012) and Kolose: The Art of Tuvalu Crochet (Māngere Arts Centre – Ngā Tohu o Uenuku, 2014).

Karl Chitham (Ngā Puhi) is Director of the Dowse Art Museum and was formerly the Director and Curator of Tauranga Art Gallery. He has been involved in the arts in Aotearoa in a variety of roles for over fifteen years. His projects have included a series of exhibitions and accompanying publications highlighting contemporary toi Māori such as Whatu Manawa: Celebrating the weaving of Matekino Lawless, Toi Mauri: Contemporary Māori art by Todd Couper and Whenua Hou: New Māori ceramics.

Damian Skinner is a Pākehā art historian and curator who lives in Gisborne. He received his PhD in art history from Victoria University of Wellington in 2006, for a thesis exploring the dynamic relationship between customary and modern Māori art in the twentieth century. He has written a number of books about Māori and Pākehā art, and Pākehā craft. His most recent book is Theo Schoon: A biography (Massey University Press, 2018).

The first meeting about this book was in December 2012, but back then we had no idea what it would turn into. It took a couple of years and many meetings and conversations with colleagues who were also invested in the importance of craft and practices of making to understand what the potential could be. At a certain point, the three of us realised there were really two parts to the book: making space for other authors to write about whatever subjects most interested them, and the three of us writing chapters that would bring into being the cross-cultural history of making that seemed most important to tell.

Making is important to many different groups in Aotearoa and in the island nations that have strong connections to this place. Every practice of making has a history and a language and a group of experts, and these histories and practices are always changing and developing. We thought: what happens if you bring these histories and practices together, and see what kind of stories can be told about them, not only on their own terms but also in the moments when they have come into contact with each other? The idea of ‘craft’ dissolves, but also comes into new focus as a central force in building the multicultural nation of Aotearoa.

We do think it is an interesting time for a new history of making. Indigenous peoples are reasserting and reclaiming practices and objects; witness all the projects that involve Māori and Moana Oceania makers visiting museum collections and learning more about old materials and techniques, but also making sure museums use the right names and cultural approaches to care for these objects. There is a new respect and affection for artisan skills; crafts that were once the domain of grandmothers are now fashionable across different age groups, and ‘craft’ as an adjective is added to all kinds of products to distinguish their quality. These and other contemporary dynamics made us want to revisit the histories of making and see if they have new stories to tell.

Wouldn’t that be amazing! The terms we use do have a huge impact on what we can know, and what we value about the things we are discussing. Moana Oceania isn’t perfect, but we found it useful in changing our perspective – now it is for our readers to see what they think.

We thought of the process as developing a kind of extended ‘brain’ made up of our respective interests and backgrounds and areas of expertise. It would be a combination of the three of us, and represent a point of view that was not the same as any one of us but also not possible without all of us being involved. We ended up naming this hybrid entity ‘Māhinnerham’, which is a combination of our surnames. It was a joke to amuse us in the dark times, but also a way to remind ourselves that we were pushing beyond our individual comfort zones.

Coconut water in honour of our location in the Moana Oceania!

What we realised early on was how much we didn’t know. As the scope of the project expanded it really demonstrated how vast this topic was and how diverse the practices and stories were that could potentially be covered in the book. It was really fantastic having the other authors involved as it allowed us to highlight subject experts who have a real passion for each of their areas of interest.

There are a lot of items that really illustrate the richness of what craft could or might be. The ones that often stand out at first glance are unusual or unique in their material or construction, but the ones that stay with you have stories that have resonance beyond the object. One of these, a tarapouahi made by Cathy Schuster and gifted to Rosanna Raymond, is beautifully made, but beyond its inherent physical attributes it is also an important symbol of the relationships forged through the common goal of caring for Hinemihi, a whare whakairo that survived the Tarawera eruption of 1886 and is now located in Guildford, England. Or the souvenirs made by Charles Chamberlain for American soldiers while stationed at Torokina Airfield in Bougainville. Made from the remnants of Japanese planes shot down during battle, these unremarkable keepsakes show how important these objects can be in talking about the histories we do not know well. There are the typefaces created by Sāmoan graphic designer Joseph Churchward that suggest the significant role migrants have played in building Aotearoa’s cultural identity, or the Formica murals created by James Turkington as an illustration of our prosperity and modern aspirations. There are so many amazing objects, practices and stories featured in the book that it is really hard to mention just a few.

The other voices in this book are so important because they prove our fundamental assertion that something interesting happens when many different subjects and ways of thinking rub up against each other. We are humbled and amazed that so many people agreed to contribute, and that they have written such powerful and detailed accounts of objects and practices within tight word limits. Many of these authors were also part of the discussions that helped us to discover what we wanted to do, and so their contributions go far beyond what you see in the pages of the book.

This has been a complicated, challenging and overwhelming journey, but we are incredibly proud of the final result. It has really pushed all those involved to rethink how we frame discussions about these types of histories and who they are for. We know it will not be what everyone is looking for in an illustrated history of ‘craft’, but we hope it will be a book that encourages readers to explore more expansive ideas of the handmade and their associated practices, to be inclusive of other cultures and ways of thinking, and to want to learn more about what makes us unique here in Aotearoa.

A landmark publication that takes another look at craft and its broader cultural role.

An illustrated history of protest and activism in Aotearoa New Zealand.

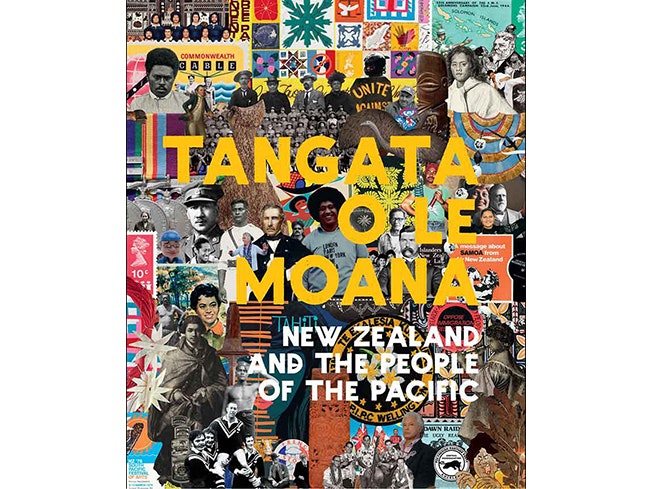

Discover a millennium of exploration, encounter, and cultural exchange in this beautifully illustrated history of Pacific peoples in New Zealand.