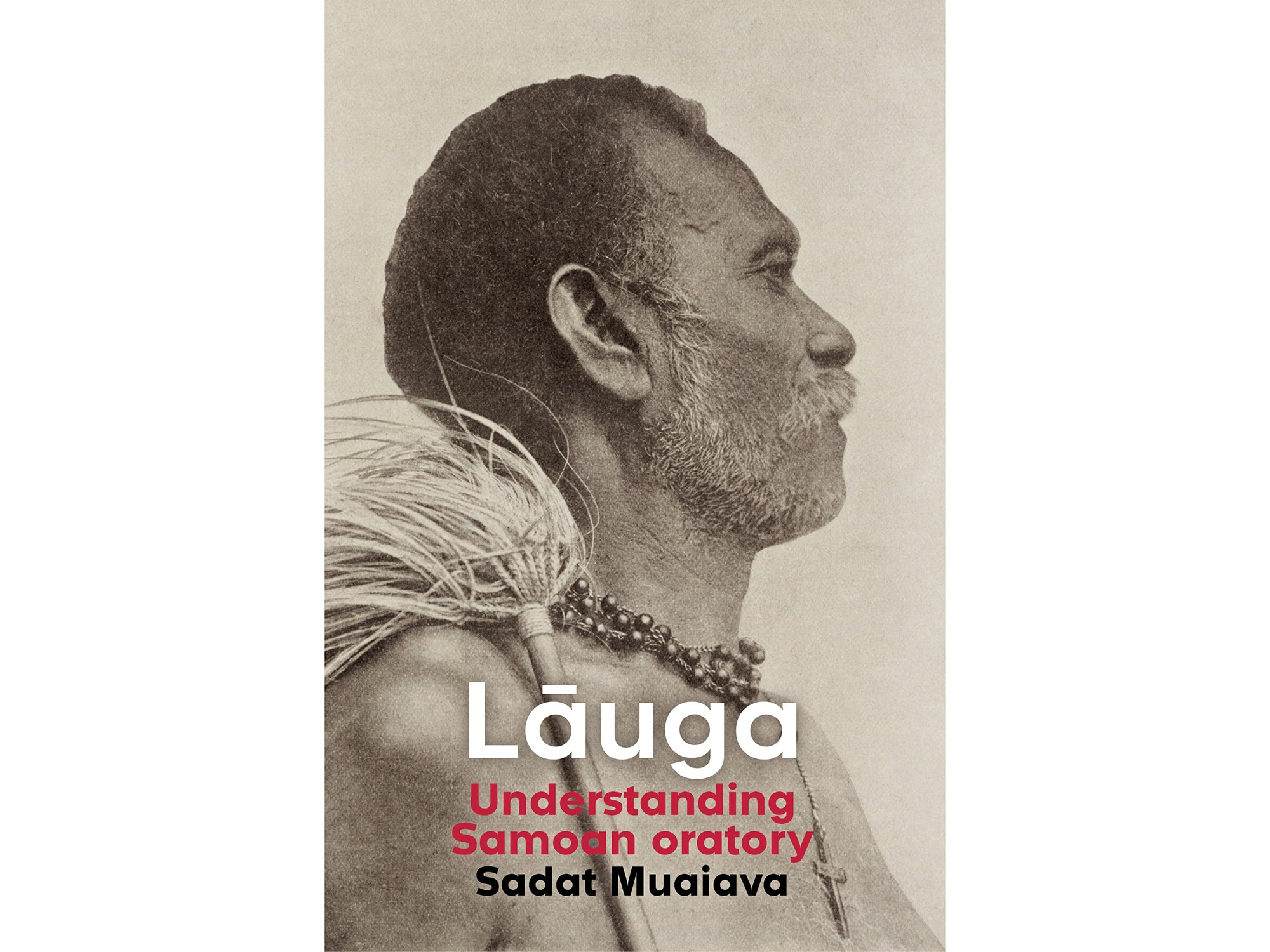

Q&A with Dr Sadat Muaiava, author of Lāuga: Understanding Samoan Oratory

Dr Sadat Muaiava discusses Lāuga: Understanding Samoan oratory with Te Papa Press.

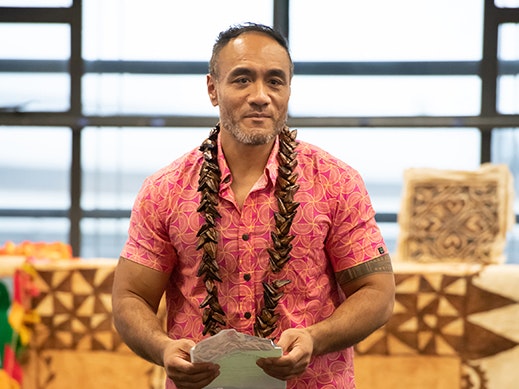

Dr Sadat Muaiava lectures in the School of Languages and Cultures at Victoria University of Wellington. He was born in Sāmoa and holds the matai titles Le‘ausālilō (Falease‘ela), Lupematasila (Falelatai), Fata (Afega), and ‘Au‘afa (Lotofaga, Aleipata). His research focus is the interdisciplinary domains of the Sāmoan (and Pacific) language and culture in the homeland, the Pacific, and in diasporic contexts. He has contributed widely and publicly in forums that discuss Sāmoan language, oratory, tattooing and history.

Sadat Muaiava. Photo by Robert Cross Victoria University of Wellington

"I think the stillness of the photos, the facial and body language, shows knowledge, mana and fearlessness. But I also see a weight of responsibility that is welcomed (moemanatunatu) as opposed to a heavy burden they have to carry. This comes in light of the idea that it is part and parcel of lāuga." – Sadat Muaiava

Where did the idea for this book first come from?

The idea for this book is more a seed I feel. It is a seed that was planted in me by my parents, grandparents and family, was watered daily and lead to the growth of an admiration and passion for Samoan oratory. I was encouraged by many people to write it, but it was a particular conversation I had with Sean Mallon on a Sunday afternoon in 2020 when we were filming for the Tatau exhibition that really got the ball rolling.

Why did you feel you needed to write it?

There’s a Samoan saying that goes “‘o le uta a le poto e fetāla‘i, ‘a‘o le uta a le vale e tāofiofi” “a wise person shares while a fool withholds”. To me personally, what’s the use of having knowledge and not sharing it? I think the idea of me sharing it with more people is that we all gain new and more knowledge from it. It’s like the parable of the talent. To understand lāuga requires a lot of exposure, something that I have been fortunate enough to have. Many of our people, however, have not had that chance. That’s also my “why”, to help others on their journey learning and understanding lāuga through a text that is accessible to them.

Did the scope of the project change as you got deeper into the project?

In some ways it did. I felt like as I was writing the book there was always more that I could have added. There’s just so much in lāuga. No text can capture its full beauty, nuance and essence. But I’m really happy with how it turned out, and the amount of knowledge that is encapsulated through not only my own experiences, but that of all the contributors.

The book is full of remarkable historic images of distinguished orators. What do you see when you look at their faces?

When I look at the pictures I always imagine what it would have been like for an orator in that particular moment in time. It makes me want to find out more about what lāuga was like in those days. I think the stillness of the photos, the facial and body language, shows knowledge, mana and fearlessness. But I also see a weight of responsibility that is welcomed (moemanatunatu) as opposed to a heavy burden they have to carry. This comes in light of the idea that it is part and parcel of lāuga.

The voices of the contributors add so much to this book. Were you struck by how candid some of them were?

Not at all. Lāuga is straight talk, but it is also known for its riddle by way of intonation and semantics. For me, the voices of contributors bring to light the many personal experiences of lāuga.

You have a busy life as a full-time academic and father of four. How did you find time to write this book?

First and foremost all praise to our Lord for the strength and knowledge. The support of family has been immense, particularly my wife Shana and children who made sure I had the time to write the book. It’s been a communal effort and one that I’ll always be indebted to.

Is there a lāuga that stands out for you as one of the most memorable you have encountered?

Even when we die we go knowing that there is always something else to learn. It’s in that acceptance that we, as the orator, begin to embrace it and become free. It’s like getting the tatau, when we give our body to the tattooist’s tools, we’re not fighting the process, and just end up loving it. Lāuga is the same. So there is no one lāuga that stands out because they’re all unique and beautiful in their own way.

Lāuga is so complex and layered. Does it in reality take a lifetime to master?

It really does. We believe that our ancestors continue to speak to us. Their speaking to us comes through their lifetime of work and tautua (service), which inform our speech in the present day. Our work will inform the next generation. So to me, lāuga goes beyond one’s lifetime.

What do you hope that new matai living outside of the homeland of Sāmoa will take from this book?

I hope they find comfort and understanding in the book, and the courage to make and create personal and shared connections with lāuga.

Are you proud of it?

The writing comes from a good place. And just the idea of sharing it with the world makes me proud of the book and the journey as a whole.

You might also like

Lāuga: Understanding Samoan oratory

Lāuga or Sāmoan oratory is a premier cultural practice in the fa‘asāmoa (Sāmoan culture), a sacred ritual that embodies all that fa‘asāmoa represents, such as identity, inheritance, respect, service, gifting, reciprocity and knowledge.

Watch: Sadat Muaiava talking about his tatau (Sāmoan tattoo)

Five Sāmoan New Zealanders share what their tatau means to them.

ʻUa faʻasoa mai e tagata Sāmoa e toʻalima mai Niu Sila le tāua o le tatau iā i latou.