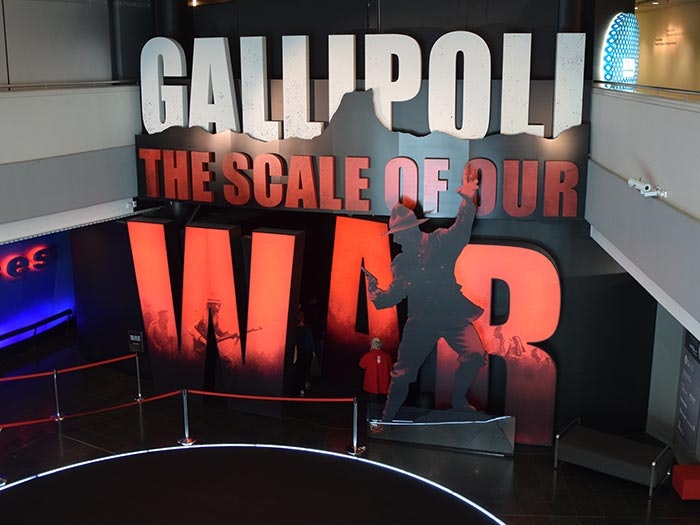

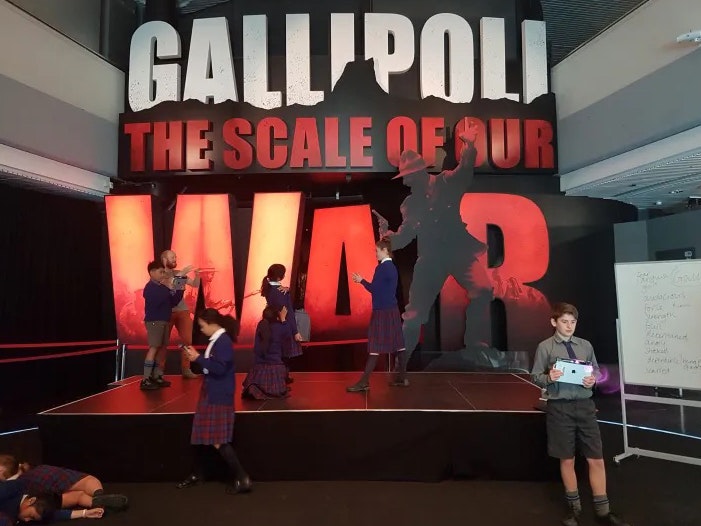

Gallipoli: The Scale of our War

Primary, Secondary

Explore our exhibition Gallipoli: The Scale of our War and the stories of those who witnessed the campaign from the front lines.

Education visit

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Puawai Cairns, Christopher Pugsley, and Richard Taylor discuss Gallipoli: The Scale of Our War with Te Papa Press.

Puawai Cairns (Ngāti Pūkenga, Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāiterangi) is Director of Audience and Insight at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, and was formerly Head of Mātauranga Māori at Te Papa.

Christopher Pugsley is a renowned New Zealand military historian and served as the Historical Director on the Gallipoli exhibition.

Richard Taylor is the founder and head of Wētā Workshop and the exhibition’s creative director.

Puawai Cairns, Chris Pugsley, and Richard Taylor.

PC: Gallipoli felt like a journey for the visitor. It was created to give the visitor a unique experience that they would not have encountered in a history exhibition before. The use of film techniques with sound and the giants acting almost like an extreme close-up at highly emotive moments, combined with strong research and storytelling craft, created a type of museum experience I have never seen before.

CP: The scale and obvious humanity of the giants. The tense, almost claustrophobic, surrounds, combined with the music and a laconic New Zealand voice. It is such a hands-on exhibition, and the two projected dioramas bring it all together. I have never seen an exhibition where almost everyone starts reading the text in detail.

RT: Due to this specific subject matter and the emotional connection most New Zealanders have to this historical event, any exhibition about Gallipoli was going to speak to the New Zealand public. I hope that the intimate way we have tried to connect audiences to the events and to characters who lived and died over 100 years ago, has touched the hearts, minds and lives of those who have chosen to visit the exhibition.

RT: Interestingly this body of work is never far from my mind. I’m often in Te Papa giving guided tours to VIPs, interested groups and friends alike. So coming back to talk more fully about the exhibition was quite cathartic in that I could share long-held thoughts and emotions with the reader.

PC: The project was all-consuming for me as I tried to create a strong research foundation in order to be able to curate stories for the show. I worked solidly for 18 months before we got anywhere near confirming the shape of the show itself but compared to the research of other people on this project, researching and establishing connections with descendants required very fast preparation. Writing about the research and process a few years after the fact has been a luxury, rounding out a process and project that meant so much to me at the time.

CP: I usually walk through the exhibition every six or so weeks. It is like entering a chapel where people are paying their respects and, intentionally or not, get drawn into looking at and reading everything. At then at the end, they are able to contribute and leave their mark with the poppies.

PC: We had anticipated that the exhibition would be popular while we were developing it but never anticipated quite how popular it has been for our audiences. It is the most successful exhibition that Te Papa has every produced and has been extended twice. The book is intended as a legacy for people who love this show and visit it repeatedly, it is also a chance to formally capture the history and development of this project before we lose the opportunity forever. And when we eventually close the show – because nothing lasts forever – the book will remain for those who wish to remember it.

CP: I met with brilliant people each week who were working their butts off and delighting in what they were doing, both at Te Papa and at Wētā Workshop. All I had to do was to keep them on track as they were discovering so much. What a team!

RT: Having Christopher Pugsley enter our lives and give us all the depth of his knowledge and wealth of his spirit.

PC: My first visit to Wene McMillin, who has passed away now. She is the niece of Thomas Haami Grace, one of the key soldiers in the exhibition who was killed at Gallipoli during the August offensive. Wene was the first descendant I made contact with. I travelled to Taupō to visit Wene with Bridget Reweti, who was on placement with me as part of her museum studies programme. Wene welcomed us into her home, told us stories of her uncle and her family, and that was the moment I felt that we were on to something special in bringing stories of Māori Gallipoli to the surface.

CP: The delight of teamwork with brilliant people.

RT: The opportunity to interact with the historians, educators, designers and curators at our national museum is one of the most rewarding experiences of my working career. To be able to access and engage with this group of people, and then to build something together with the collective intent that we did over that short period of nine months, is nothing short of extraordinary to me.

PC: Our commitment to storytelling was our common ground, even though we all had different methods in creating those stories. There was creative tension at times but also respect for each other and what we all brought to the table. Working on the exhibition was a formative experience for me as a curator beginning to find my confidence. Working with highly experienced curators like Kirstie Ross, Stephanie Gibson and Michael Fitzgerald, testing my research mettle with Christopher Pugsley, and keeping on my creative toes with Richard Taylor and our designers, are experiences that have shaped my career.

PC: There are lots, but everywhere the story of the Māori soldier comes to the fore is something I’m deeply proud of. The giant depictions of Friday Hawkins and Rikihana Carkeek, the sound of the haka, waiata and the karanga in your ears, the words of Te Rangi Hiroa and the Padre Henare Te Wainohu, and even the small basin at the conclusion of the exhibition so visitors can whakanoa – all these things were important to build the Māori presence in the show.

RT: The labyrinthine qualities of the layout. Ben Barraud, the senior designer from Te Papa, designed something wonderful so that when a visitor steps into the exhibition, they explore the content through a labyrinth-like layout. In turn they hopefully have cause to forget modern life’s worries, what is happening outside of the museum, and lose themselves in the stories of the people that we share throughout the exhibition.

CP: I believe all of it works brilliantly but the Fenwick diorama always makes me pause, Lottie makes me cry, and I cannot believe that we managed to show the impact of the various weapons in such stark detail and yet so sensitively.

CP: I’ve been overwhelmed at visitors meeting the people on display, both giants and otherwise, and realising that they are like people they know; the sense of identification with someone who is so like your grandfather or family member or friend.

PC: The layers of information in the show, which make it possible for visitors to discover something new each time, has always been surprising to visitors I’ve guided through. I’ve taken groups through who have been a number of times but they get blown away at how much more there is to discover when taken through by a curator. I find that very gratifying.

RT: We challenged ourselves in designing this exhibition so that, regardless of an individual’s level of interest on entering the first room, the stories of the soldiers and nurse that we share would guarantee an appropriate level of connection. Whether it be young children, governmental delegations, VIPs, or elderly friends, I would like to think that everyone who enters the exhibition leaves with a deeper understanding, and, more importantly, a deeper connection to the men and women that served in this campaign over a century ago. Some people leave in tears, some people leave wanting to go back through again – but whatever the level of emotion, it seems most people leave feeling more connected to this important event in New Zealand’s history, and feel they know more about the people whose stories we have shared.

RT: As a New Zealander I feel very proud how we as a country acknowledge this conflict so many years after the fact. We haven’t allowed it to become a quickly fading memory told through sepia-coloured photographs of a time and people long gone. We keep it relevant and important for a new generation of young Kiwis growing up who need to know about their past – of conquest, triumph or defeat, and the resulting trauma that can travel across generations and leave its mark today as it did all those years ago.

CP: I hope that this exhibition is able to continue, to reach more people.

PC: We should remember that each of those Māori boys that died over there or was affected by their time at Gallipoli, was cherished by their families and their people. I would like each of them to have their story known so we are all cognisant of the loss and the impact of that battle.

CP: I have been privileged to meet and talk with the families of all the giants and interviewed and talked with many of the voices that are heard in the exhibition. I keep finding out more about men and women I would have loved to have met. Everyone has a story to tell, so each is important to me.

PC: A mother who said farewell to her child as they embarked for the war. I cannot bear the thought of saying a similar goodbye to my own child.

RT: I probably identify with nurse Lottie Le Gallais, who goes to Gallipoli in service to the wounded men fighting on the Peninsula and hoping to see her brother Leddie. I am pretty sure that is the sort of thing I would wish to do in a situation such as this. I would like to think that I would be desiring to look after others and help those badly in need.

RT: A greater depth of historical knowledge, of course, as shared through the incredible writings of Michael, Christopher and Puawai. It would also be lovely for people to see and learn about what it takes to create an exhibition like this one, to hopefully better appreciate the creative endeavour required to bring an exhibition such as this to life.

CP: Thoughtful memories of a brilliant exhibition that made them more aware of who they were as New Zealanders.

PC: The work that went into creating this show was immense and made by many, many hands. I hope it sparks an interest in understanding crafting stories in museums, or a desire to research their own stories and histories.

Primary, Secondary

Explore our exhibition Gallipoli: The Scale of our War and the stories of those who witnessed the campaign from the front lines.

Education visit

Read blogs about behind-the-scenes work that goes into this exhibition, research into people and places, and direct connections with people in Aotearoa New Zealand.