Q&A with Michael Szabo, author of Wild Wellington Ngā Taonga Taiao

Michael Szabo discusses Wild Wellington Ngā Taonga Taiao with Te Papa Press.

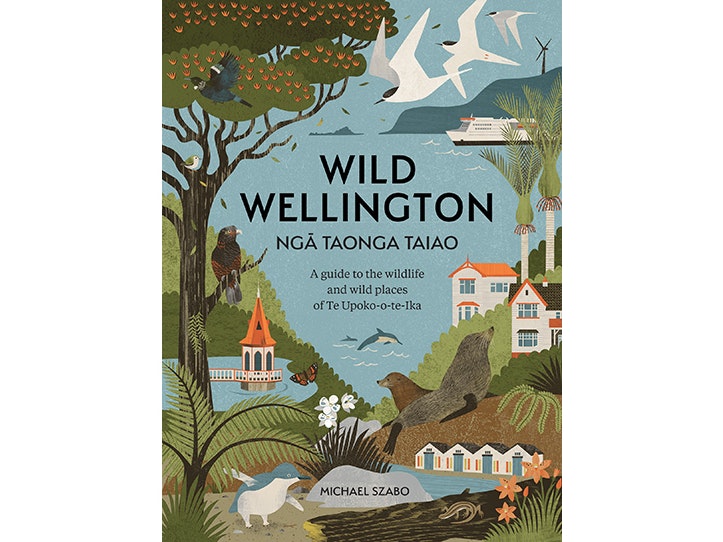

Michael Szabo is a long-time Wellington resident and writer and well acquainted with the region’s wildlife. He is editor of Birds New Zealand magazine and a contributor to New Zealand Birds Online. He was principal author of Native Birds of Aotearoa (Te Papa Press, 2022), Wild Encounters: A Forest & Bird guide to discovering New Zealand’s unique wildlife (2009), and has written for New Scientist, New Zealand Geographic, the Sunday Star-Times and Wilderness.

Michael Szabo and Wild Wellington book cover

"I was inspired by similar nature-related books that my parents bought for me and my siblings when I was a child and that has helped to give me decades of enjoyment and appreciation of nature. " – Michael Szabo

How did the idea for Wild Wellington Ngā Taonga Taiao come about?

When I moved to Wellington in 2003, I couldn’t find much easily accessible up-to-date information on the wildlife and wild places of the Wellington area in one handy place. So I set out to find out about them for myself. While I was working for Forest & Bird, I started the Going Places column in their magazine and got into the habit of photographing what I saw when I travelled around the country, including Wellington. After a few years I was able to interest a publisher in producing a book of the collected Going Places columns (Wild Encounters, 2009).

As I explored more wild places in the Wellington area and took more photos, it occurred to me that I might eventually have enough to produce a book solely focused on the Wellington area. After writing Native Birds of Aotearoa for Te Papa Press (TPP) in 2022, I discussed these ideas with the TPP team, which led to a proposal for this book. TPP was also keen for a book that provided a link between the museum’s Te Taiao exhibition and the wildlife and wild places of the wider Wellington area, Te Upoko-o-te-Ika.

What is your relationship to the region and its wildlife?

After my first visit to Wellington in 1990, when I lived in Auckland, I regularly visited the capital over the next decade and managed to get to some of the better-known wild places such as the south Wellington coast and Kapiti Island. In the years after I moved here, I had three young children, so we often went out exploring wild places from the city either up the Kapiti coast, Hutt Valley or across to the Wairarapa. Through my work at Forest & Bird I also met various people working in conservation or involved with community nature restoration projects who were generous in sharing their knowledge and insights.

Living near the beach in Island Bay also meant that I got to see the establishment of the no-take marine reserve there in 2008 and have watched it change over subsequent years. I’ve also helped plant native species on the Island Bay sand dune with my children and we’re supporting the predator free efforts and planting native species in our garden. As a member of Birds New Zealand, I’ve helped organise regular pelagic birdwatching boat trips out into Cook Strait since 2016.

How were mana whenua involved in the development, production and naming of this book?

Te Papa Press shared the book proposal and pages throughout development to rangatira at Te Āti Awa and Ngāti Toa with an invitation to provide introductory texts on the sites in their rohe. They very generously responded with their eloquent texts, which appear at the start of each of the book’s four sections, and Te Āti Awa provided the karakia. These contributions provide insights into the culture and history of the area, making it an even richer book. To further acknowledge our bicultural history and in line with Te Papa style, the 500+ species names in the book are given in both Te Reo and English, or very occasionally a Latin name where no other was available.

You just mentioned that over 500 species are covered in the book … how did you start to write with such a huge cast of characters?!

Each chapter has a slightly different focus, showcasing different wildlife or habitats. For example, at Zealandia the focus is on the native forest birds and the reptiles, at Taputeranga Marine Reserve it is on the coastal marine wildlife, and at East Harbour Regional Park it is on the tawhai beech forest and native orchids. Over the 30 chapters, that’s an average of about 17 species per chapter, but of course there are many more species than that to be found at each site!

I’ve been very fortunate to be able to learn from others with more knowledge of where to look for certain species or habitats, and over time I’ve been out and explored these wild places repeatedly for myself. As editor of the Birds New Zealand magazine and through administering the New Zealand Birders Facebook group I’ve been able to share interesting bird sightings and direct people to the best places to see certain species. In recent years eBird and iNaturalist have become invaluable resources, where people can report their sightings of birds and other wildlife and have them verified by scientists. I’ve also learned from other Facebook groups such as Whale and Dolphin Watch Wellington, Wild Plants of Wellington, and New Zealand Native Orchids.

Te Papa’s Natural History team helped with my research and I learned something from all of them, especially about the ferns, reptiles, fishes, insects and shellfish. I already knew a fair amount about the native birds and how the Wellington area has an impressive diversity of them, but I’ve been struck by how fortunate we are to also have so many fern and reptile species in the area. The ferns are ubiquitous while the reptiles are currently more localised, mostly on the islands and at Zealandia. Leon Perrie and Lara Shepherd (ferns) and Colin Miskelly (reptiles) have a very detailed knowledge of these groups and were very generous in sharing that knowledge and their insights with me for the book.

How did you select the 30 locations?

The Wellington area has many of the geographic features that typify Aotearoa so the sites featured in the book are a representative selection, covering a broad range of species and habitats. That means there is something for everyone, from short walks in urban parks to longer hikes up and down maunga, and short ferry trips to longer pelagic seabird watching trips at sea.

Accessibility and free entry was also a consideration because I didn’t price to be a barrier to experiencing to what the region has to offer. The Wellington area has good public transport network coverage with many electric buses and trains, which means all but a couple of the sites in the book can be reached by public transport. The three island sites all require a short ferry ride. All the mainland sites are free to enter except Zealandia.

Almost all of the photographs in the book were taken by you … do you have any tips for readers who might also want to photograph/record the wildlife they discover?

The first priority is always to obey the rules at each site and consider the welfare of the wild species within them, whether it’s a wētā or a maki orca. I find that the more I know a species, the better my photographs are likely to turn out. If you understand the behaviour of the kārearea New Zealand falcon, you will be more able to anticipate a bird’s next move and be prepared to take photos of them doing different things – their kek-kek-kek call can tell you when they’re around, and some of their behaviours such as preening and prey-swapping can make for great photos.

There’s no substitute for patience. If you are prepared to wait, you are more likely to get the shot you want or see interesting behaviour. It’s also worth looking at other people’s photos online or on social media. That can help you plan shots and you can usually ask other photographers where or when they took a particular photo. The more you can get out and take photos, the better your photography is likely to become.

You write about Wellington Te Whanganui-a-Tara as the ‘nature restoration capital’, what are the best examples of this?

Aotearoa New Zealand is a ‘nature restoration’ super power with so many good examples around the country. Here in the Wellington area, there is a ‘critical mass’ of initiatives that range from site-specific restoration projects at Zealandia, the main islands (Kapiti, Mana, Matiu Somes) and the Taputeranga Marine Reserve to larger and more complex projects that target more extensive areas such as Predator Free Wellington and the Kiwi Capital Project.

There are also new visionary projects on the horizon, such as the proposal to establish a predator-free fenced ecosanctuary at Puketahā near Wainuiomata that is 15 times larger than Zealandia, and includes plans to reintroduce kākāpō, another kiwi species, and kōkako.

What are two or three key things you write about that you really hope readers are lucky enough to see or experience?

It’s not difficult to see a flock of kākā or tūī at the Botanic Gardens but if you want to see a different sort of spectacle, there’s the winter fur seal haul out at Te Rimurapa Sinclair Head, and the chance of seeing large pods of dolphins off Houghton Bay or Island Bay in summer.

Sites such as Zealandia and Kapiti Island have a spectacular variety of native bird life in a native forest setting, but if you want to see breeding seabirds and waterfowl the Waikanae Scientific Reserve has both in good numbers.

For flowering native plants, there is the spectacular flowering of kohekohe at the Botanic Garden and Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush in May-June, and the sublime flowering of the northern rātā and various native orchids at the East Harbour Regional Park in late spring and early summer. If you want to see skinks and geckos it’s best to visit Mana Island, and for tuatara go to Zealandia or Matiu Somes Island.

What does the future hold for Wellington wildlife?

Kiwi-nui North Island brown kiwi are already spreading out from the Mākara hills towards Wellington’s eastern-most suburbs, so over time more will be seen at sites such as Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush. The ‘halo effect’ of Zealandia can be felt across the city and beyond. We know from regular surveys that native birds such as kākā and tūī are increasing well beyond Zealandia. Marine life is also spreading out from the Taputeranga Marine Reserve along the south coast into the harbour, and ditto from Kapiti Marine Reserve along the Kapiti coast.

One of the consequences of nature restoration is that people who own a dog should be aware of the need to keep their pet on a lead in and around wild places like Ōtari-Wilton’s Bush because in the next few years we are going to see more kiwi reaching the periphery of the capital’s eastern suburbs, such as Karori. As more kororā little blue penguins breed in nest boxes at sites around the harbour and on the south coast, dog owners also need to ensure that their pet is always under control at coastal localities such as Greta Point, Miramar Peninsula, Eastbourne, and the south coast.

What do you hope readers will take from reading and using this book?

I hope it helps readers living in the Wellington Te Upoko-o-te-Ika area to discover and connect with nature in new ways at new places. Whether they live in Wellington, Hutt Valley, Wainuiomata, Porirua or on the Kapiti Coast, it’s worth taking time to visit some of the wild places in other parts of the area that they’re perhaps not as familiar with. I also hope that experiencing more of our wildlife and wild places will encourage more people to get involved with local nature restoration projects and to plant more native species in their gardens. I was inspired by similar nature-related books that my parents bought for me and my siblings when I was a child and that has helped to give me decades of enjoyment and appreciation of nature.

For visitors from further afield, I’d say it’s well worth taking the time to explore Te Papa’s Te Taiao exhibition plus at least one of the nearby wild places included in the book such as the waterfront walk, Wellington Botanic Garden or Zealandia. For someone who repeatedly visits the Wellington area, try to get to more of the wild places in the book each time and over the years they could perhaps visit all of them. In my experience you won’t see everything in one visit, so repeat visits at different times of the year are rewarding.

You might also like

Wild Wellington Ngā Taonga Taiao: A guide to the wildlife and wild places of Te Upoko-o-te-Ika

What to see where, when, and how in the Wellington region.

Te Papa Te Taiao Nature Series: Native Birds of Aotearoa

A handy introduction to the unique birdlife of Aotearoa New Zealand, for the backyard, bach, and backpack.