There are ghosts in this place.

They whisper, tormenting, tearing at my insides, screaming accusingly, do you remember me?

Dressed in giant red flowers, floating on a tropical twist, they sing to me.

Loud, boisterous, hymns of prosperity, promised liberation and a love beyond their grasp.

Telling tall tales of sex under palm trees with the sons of church ministers, surrounded by the aroma of tyre rubber, kerosene, and mulberry bark.

Away, I implore them, but they refuse and continue to whisper to me.

They once walked these streets, in high heels, torn attire in the fading light of a migrant dream.

Adored in a brown spotlight for men’s night-time consumption, spending their days on the factory floor.

There are ghosts in this place.

Like Our Ancestors poster, 1998, New Zealand, by New Zealand AIDS Foundation, Arjan Hoeflak, Mariano Vivanco, Harold Samu. Gift of New Zealand AIDS Foundation, 2019. Te Papa (GH025369)

What does it mean to be haunted by the ghosts of a history that was never written?

We, as Pacific people, are accustomed to having our lives and experiences becoming their stories, written about us, without us, and for someone else’s consumption. The Orientalist brush that rendered us dusky maidens, noble and ignoble savages also morphed us into capitalist fodder for New Zealand’s colonial ambitions.

Pacific narratives in Aotearoa follow a familiar but all too singular line – migrants, factory workers, sports people, entertainers, redeemable scapegoats – but, what of us who seemingly do not exist in the canon at all?

Growing up Samoan in South Auckland as an up and coming queer man in the ‘90s, my history it seemed, from every angle, was written for me but without me in it.

Our people, at this time were recovering from the trauma of the Dawn Raids, coming off the factory floors to excitedly and willingly drape themselves in assimilationist respectability within this settler-colonial state.

During this time, our community began basking in the glory of firsts – the first New Zealander to win a World Athletics Championship was Sāmoan, the first New Zealander in umpteenth years to top the US music charts was Sāmoan. The first Pacific Islander Member of Parliament was, again, Sāmoan.

At the same time, New Zealand’s queer community had found its voice, and were picking up the pieces of a group shattered and ravaged by the worst horrors of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Although New Zealand was spared the absolute worst of it, its impact on our queer community was nonetheless horrific.

In the middle of this, I, a Sāmoan gay, queer man, came to know myself as not quite Pacific enough or not qwhite queer enough to be considered a central concern of the two marginal communities I was sorted into.

Pacific narratives in Aotearoa follow a familiar but all too singular line – migrants, factory workers, sports people, entertainers, redeemable scapegoats – but, what of us who seemingly do not exist in the canon at all?

My queer self came into its own at the ascendency of the time of the Hero Parade, when new queer heroes were beginning to take flight. I recall vividly standing on the Ponsonby Road footpath in my bright aloha shirt screaming my applause at Georgina Beyer, the first trans Member of Parliament our country and the world had ever elected to a house of government.

Buckwheat and Bertha, children of Sāmoan migrant families, were hosting a cooking show on Tagata Pasifika decked out in full drag on a Sunday morning as many of us shuffled between to’ona’i (Sunday lunch) and Sāmoan churches. Often, the evening prior, Pacific Islander drag queens of all shapes, sizes, and flavours were tearing up dance floors and stages across Auckland’s night club scene.

I was in high school during these fast-moving times. I attended a Catholic all-boys school with a group of self-identified gay friends and we navigated together the stresses of being gay, Catholic, Sāmoan/Cook Islander/Māori whilst surrounded by blokey boys and a religion that considered us unwanted specks of dirt on a cishet windscreen.

Most of us were raised with these blokey blokes (some of them our actual brothers) in Catholic primary schools. However, at this point of our lives, they were most definitely headed in the opposite, heteronormative direction, from us.

At school, I learned about the World Wars, the Civil Rights Movement in the US, got turned off from Newtonian physics, and chemistry, all the while leading in drama productions, debate teams, and partaking in Shakespeare festivals. The standard queer experience of being teased, sometimes bullied (physically and verbally) was a reality, but it wasn’t all doom and gloom.

My friends and I often flipped the script and started beating our own flamboyant drum of queer defiance. We fought other boys, each other, draconian school rules, and draconian school staff, and built alliances with more progressive minds as we went. By the time we finished, a whole new generation of queer Pacific bodies were claiming space at this very Catholic, very Pacific learning institution.

My world at home was far less glamorous. It was one of economic hardship, state housing, transgressive beauty pageants, community intrigue, fashion wars, and watching countless numbers of fa’afafine with dubious immigration status working the streets of New Zealand’s Queen City in search of a buck and a prayer.

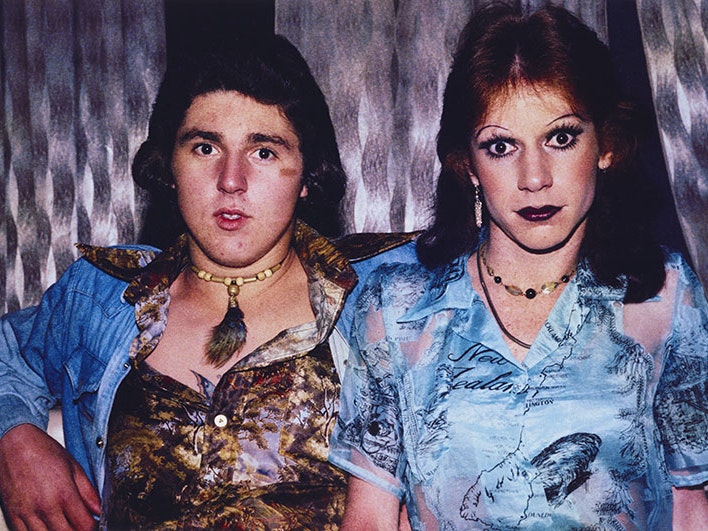

Queens of the Pacific poster, late 1990s, New Zealand, by New Zealand AIDS Foundation, Arjan Hoeflak, Mariano Vivanco. Gift of New Zealand AIDS Foundation, 2019. Te Papa (GH025370)

These fa’afafine, transient in many ways, represented largesse familial dreams of their own. Although some were shunned by families for being fa’afafine, others were readily put to use in a transnational game of remittance roulette. The majority I knew had moved to New Zealand on their own. While here, they built communities around each other, contributed to many Sāmoan churches (who in turn shunned them), community events (where they remained invisible), and provided entertainment (ridiculed) and decorative labour (exploited) for friend and family groups with very little financial reward.

I know I wasn’t meant to really know what was going on, but sometimes I found myself riding in the back of cars with my mum and her fa’afafine friends as they would pick up and drop off girls who were working the back alleys of K’Rd. Eventually, the trips would become more localised, without parental knowledge (or consent) as my adolescence gave way to early adulthood. Then, I found myself walking streets closer to my South Auckland childhood home at night, with my friends, partaking in the devil’s night time game of sexcapades, hunting and being hunted by “straight” Pacific men.

And what a sight some of my friends and older fa’afafine were on these heady nights. Decked out in full gowns sometimes, elongated legs in high heels that would clickity-clack against the dark night. Long flowing tresses, and make-up from L’Oréal or her less expensive friends provided blush, eyeliner, foundation, and hair dye in some cases. Their laughter would drown out the silence of the loaded evening, carrying us toward the early hours of the morning as many of us just drank in cars, trying to numb the pain from the struggles of the light.

Many also perished. Physically, financially, and mentally, overcome by the pressures of living as a migrant other, all the while finding little reprieve from a cisnormative New Zealand nation-state that paid no mind to liminal gender or sexuality, even if there was a common cultural acceptance around these deviant bodies.

I remember one incident, where a good friend of my mother’s explained how she ran from the police. These were pre-legalisation-of-prostitution days, and “soliciting or selling sex services” (whatever that meant) was still illegal. As she ran from the police, she found herself tripped up by the uneven pavement. She took a hard fall and as the police caught up to her and began to handcuff her, breathless, she couldn’t think of the English word for being winded so pleaded to the coppers: “please, wait, wait….. I’m, I’m mōrē, I’m mōrē.”

The Sāmoan word for winded is mōlē.

She found herself at the back of a police vehicle that night, winded and having to dance the dance of the New Zealand judicial system over the following weeks.

Today, as I watch neighbourhoods around South Auckland begin to gentrify, these stories have begun to fade from our collective memories as an unapologetic, cosmopolitan minded Pacific queer youth take over. Theirs is a world of vogue balls, not just gender bending, but smashing cisnormative patriarchy – determined to carve out their own space in our narrative.

I admire them, their energy, their unflinching principles, their visibility.

But as I walk these much more respectable streets today, I am sometimes filled with a sense of void and emptiness. My world of growing up queer and in South Auckland. Or, moreso, the world of my queer, gay, fa’afafine elders, who never made it to any sort of redeemable light. Their struggles, their perseverance, their mana, their daring has been lost to the vagaries of time, falling victim to less than secure communal memories.

But I hear them, I see them still, these ghosts of a Pacific, Sāmoan queer South Auckland past.

They whisper to me, I hear them calling, asking me: where is my place in our community’s past?

I have no answer for them.

I see their light, I feel their power, and I am urged to LIVE to honour their marginality. I am their successor.

There are ghosts in this place.

Born and raised in South Auckland, Seuta‘afili Dr Patrick Thomsen is of Sāmoan descent and a Lecturer in Pacific Studies at the University of Auckland. As a newly-emerging Pacific academic he is also a well-known social commentator, researcher, freelance writer, and activist concerned with SOGI Rights across the Pacific and in New Zealand.

He is also currently the Principal Investigator for the Manalagi Project, New Zealand’s first Pasifika Rainbow health and wellbeing project, and is the Pacific co-lead for the Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI).