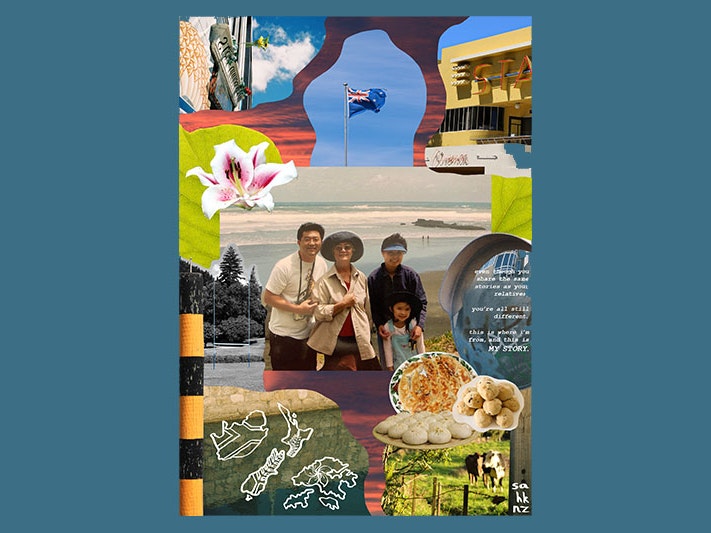

Koreen Liew-Young’s story, 2022. Illustration by Mengzhu Fu, courtesy of the artist

My earliest relative to arrive in New Zealand was my great, great grandfather who came from Canton, China to Wellington in 1896, so that makes me a fifth-generation Chinese-New Zealander.

Growing up, I had this complex about not being a “true” Chinese person because I didn’t speak a Chinese language. My mother lacked confidence to speak Cantonese and her generation spoke English as their primary language. Most of my cousins couldn’t really speak Cantonese at all. The only ones who mainly spoke Cantonese were my grandparents, who lived in another city. When they passed away, so in a sense did my connection to the language. I had also resented my ethnicity because of all the racism and stereotyping I’d experienced. I looked different to other New Zealanders and I felt many new migrant Chinese didn’t consider me “Chinese” enough. I didn’t know where my place was; I was in this weird void in the middle. I joked about being a “banana” (yellow on the outside and white on the inside) to deflect any insecurity I had. But this perception of myself, was soon challenged.

At university, I started to explore my cultural identity and the history of Chinese people in New Zealand. I travelled to China in my 20s to see our ancestral villages and explore my heritage on a New Zealand Chinese Association organised tour. Here, I was able to see a glimpse into the simple and busy life which my ancestors would have had to live through. I started to find an anchor for my life going forward, even if I didn’t fully identify with it.

And then in my early 30s, I married my husband (Julian) who is of Malaysian-Chinese descent. He was passionate to study Mandarin and wanted to immerse himself in China to learn … and he wanted me to go with him! I felt nervous to go, wondering if I would be pointed out to be the fraud I’d always feared to be. But I went anyway.

It was hard and I often felt out of my comfort zone. Not being able to converse in Mandarin to do the simplest of things, like buy fruit, was initially stupidly difficult. I felt like I had made a mistake in coming. But I was determined to make the most of the time that we had in Beijing. I diligently studied Mandarin and took every opportunity I could to talk to people. I went every day to buy fruit to practice my text book phrases. Funnily enough, these phrases were about buying bananas! I talked to random people everywhere and found so many strangers willing to engage with my pidgin Mandarin. Some even took us on guided tours and out to restaurants. I loved my time in Beijing.

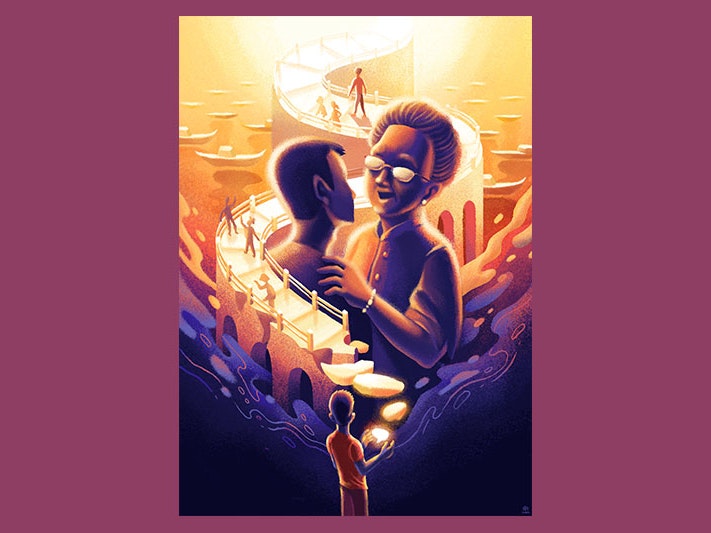

Mengzhu’s illustration came from a day when I found a balloon vendor while biking to class. I fell in love with a giant oversized rabbit balloon he had for sale and now had enough Mandarin to communicate with the vendor to buy it. It was such a simple and playful act, but it reminds me of the wholesome joys that connecting with your culture can bring. Putting all those eye-opening experiences under my belt, I returned to New Zealand with a greater acceptance of myself and a link to my heritage.

Now, even though I can only speak Mandarin like a pre-schooler, I can teach my son some basics and give him a foundation. I hope my little sixth-generation Chinese-New Zealander will be more confident in who he is and appreciate his connection to the previous five.

– Koreen Liew-Young

Illustrator’s process and reflections

Instead of a comic or classic portrait, I decided to do something more conceptual. It was this line in her story that inspired this piece: “I was in this weird void in the middle.” I think the experience of liminality, inbetweenness is so common and relatable among diasporic Chinese folks and multi/bilingualism is also part of that. I decided to turn to our characters/words for thinking on that experience.

The character is a 篆书 (seal script) version of both 间 and 门, which I thought was perfect in representing this experience. 间 means between, like 中间 or 之间, but it’s also used to indicate time, 时间. The “日” is subtle and hidden in the bike. Getting to know this character’s etymology helped me to understand something quite profound – that is, this character represents a door, 门, and it is that space in between that allows for light to enter, symbolised by 日 and at times in the past, 月 – the sun and the moon. Liminality, or that space in the middle, is then a space of possibility.

The bike represents a journey of balance, often our experience is an exercise in balancing multiple worlds and languages, and it’s based on photos that Koreen sent me of her time in Beijing – cycling in Beijing is also a fond pastime of mine! The bike cycles through the square space you write in when learning to write Chinese characters.

The balloon is also from a reference photo she sent me and I had put it in there to bring a joyful and celebratory mood to the image. She has story behind it too! The background colours are colours of sunset, a liminal time between day and night, where the sun and moon sometimes can both be seen (to honour the history of the character 间) and to highlight the beauty of liminality, where many colours can interact and co-exist without competition. I wanted to show how this “weird void in the middle” can also be a (re)generative space where light shines through, a door.

– Mengzhu Fu