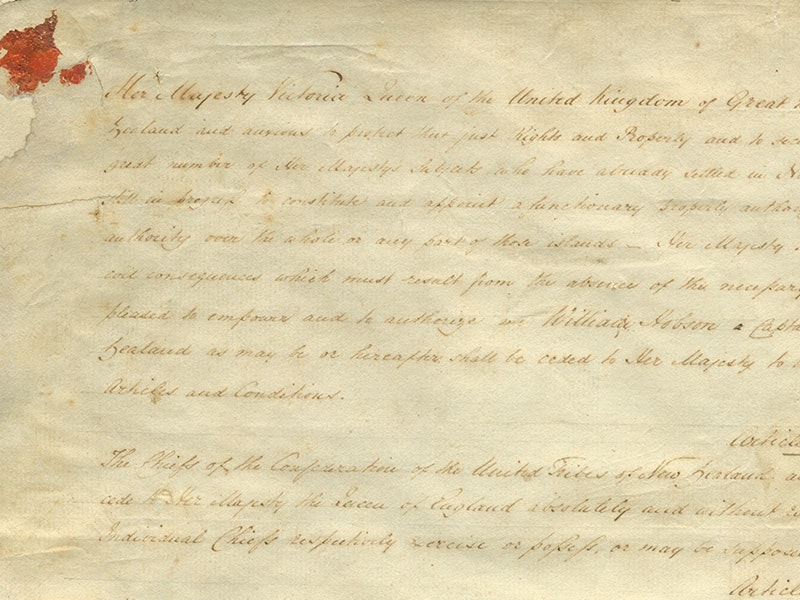

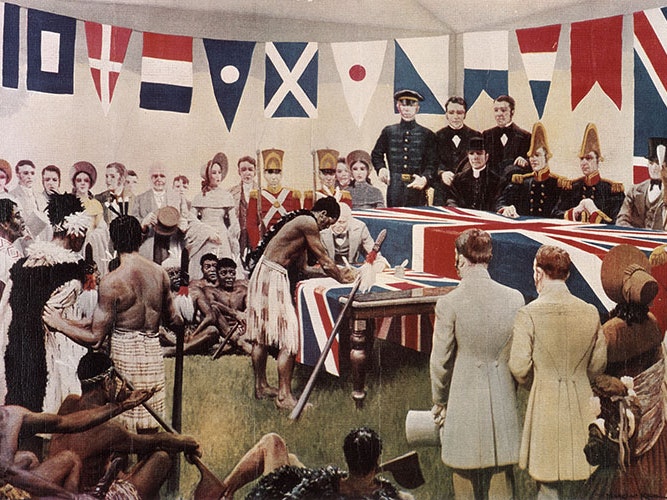

The full text of Te Tiriti o Waitangi | The Treaty of Waitangi

Read the original English and te reo Māori texts of Te Tiriti o Waitangi | The Treaty of Waitangi, and a contemporary translation of the te reo Māori.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

For many reasons, what Māori and British actually agreed to in the Treaty has been unclear.

Ahakoa he motu tū wehe, nā ngā uaratanga ka honoa.

Although close islands stand separate, they are linked by necessity.

There were two versions of the Treaty – one in English and one in Māori. They are not exact translations of each other.

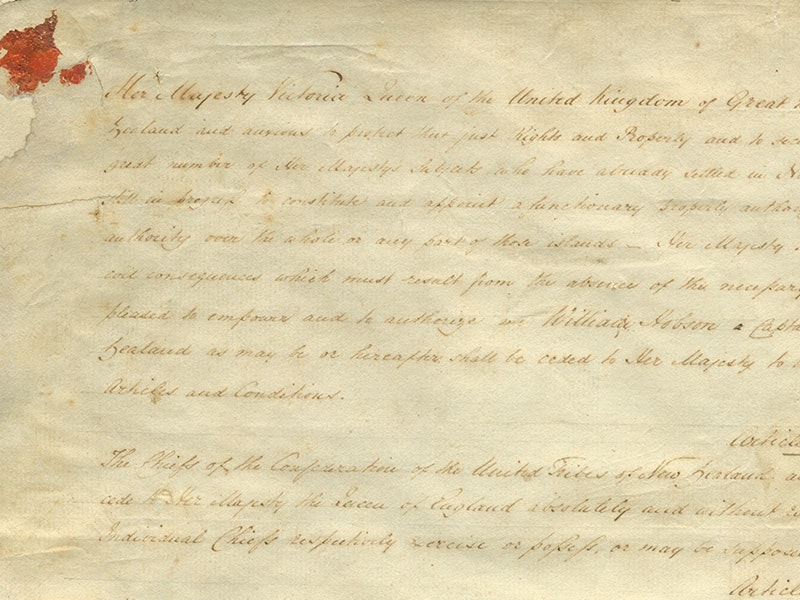

Those who signed the Treaty brought different experiences and understandings of certain words to the signing.

When the British representatives took the Treaty to different Māori groups they possibly introduced it differently, and their explanations no doubt varied.

In the English version of the Treaty, Māori give the British Crown ‘absolutely and without reservation all the rights and powers of sovereignty’ over their lands, but are guaranteed ‘undisturbed possession’ of their lands, forests, fisheries, and other properties.

In the Māori version of the Treaty, Māori give the Crown ‘kawanatanga katoa’ – complete governorship. And they are guaranteed tino rangatiratanga – the unqualified exercise of chieftainship over their lands, dwelling places, and all other possessions.

These different promises don’t sit alongside each other easily.

The reasons why chiefs signed the Treaty varied from region to region. They were influenced by the aims of iwi and hapū and the explanations given by negotiators.

Ngāti Whātua wanted to forge a relationship with the Crown that would benefit both the iwi and settlers. They wanted the chance to have the governor and the capital of New Zealand on their lands in future.

Te Āti Awa and other Wellington iwi wanted controlled settlement and the benefits it would bring. Chiefs in Wellington were so surprised by the hundreds of settlers that they asked if the whole English tribe was migrating.

Ngāi Tahu rangatira Hone Tuhawaiki wanted the protection of the law, as well as guarantees about land. For his Treaty signing he wore the full dress staff uniform of a British aide-de-camp with gold lace trousers, cocked hat, and plume.

Ngāti Toa wanted to maintain the position they had gained in the region, and to benefit from the skills and new technologies that Europeans would bring.

Fears that the French had designs on New Zealand also played a part in some tribes agreeing to the Treaty. The missionaries argued that a British administration would be better than a French one.

Some iwi, especially Ngā Puhi, saw the Treaty as a covenant, a spiritual bond with the British Crown. A number of missionaries encouraged this view.

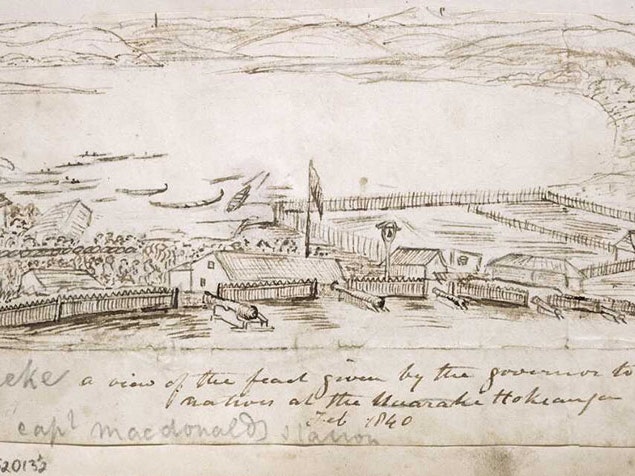

In 1860, 20 years after the original Treaty signing, Governor Gore Browne invited some 200 Māori leaders from all around New Zealand to a conference at Mission Bay, Auckland.

The aim of the three-week conference was to secure Māori loyalty. The Treaty was read again to the assembled leaders and its benefits explained. The hui ended with chiefs declaring they were ‘pledged to each other, to do nothing inconsistent with their declared recognition of the Queen's sovereignty, and of the union of the two races’, Māori and Pākehā.

This pledge came to be known as the Kohimarama Covenant.

Rangatira saw the conference as a recognition of their mana and authority, and a hopeful sign that they would participate in decision-making – as they expected from the Treaty’s terms.

The Governor agreed to their request for an annual conference, but no further conferences were held as the country moved to war.

His Excellency Colonel Gore Browne & Family, photographer unknown, about 1860, carte-de-viste. Te Papa (O.013133)

Browne was governor from 1855 to 1861. During that time a Māori king was set up in Waikato, something Browne saw as incompatible with British sovereignty. War linked to dubious land transactions also broke out in Taranaki. Browne relied on the Treaty to get rangatira loyalty and support for government policy. Rangatira pledged loyalty but were critical of Browne’s policy.

Memorial portrait, Queen Victoria, 1901, England, by Walery. Te Papa (GH003160/1)

Many Māori felt they had a special relationship with her.

***

This content was originally written for the Treaty2U website in partnership with National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa and Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o Te Kāwanatanga in 2008, and reviewed in 2020.

Read the original English and te reo Māori texts of Te Tiriti o Waitangi | The Treaty of Waitangi, and a contemporary translation of the te reo Māori.

The British government appointed William Hobson as consul to an independent New Zealand. It sent him here with one goal – to get Māori to sign over sovereignty of all or part of New Zealand to Britain.

Over 40 rangatira signed the Treaty at Waitangi, among them many who had signed the Declaration of Independence. Their agreement was important, but Hobson wanted a lot more signatures so he could confidently claim British sovereignty over New Zealand. To get those signatures, he took the Treaty on the road.