Rita Angus: New Zealand Modernist

Rita Angus created a distinctive vision of a new, modern New Zealand. This landmark exhibition celebrates 40 years of her work.

Closed

18 Dec 2021 – 25 Apr 2022

Exhibition Ngā whakaaturanga

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

This audio descriptive introduction to Rita Angus: New Zealand Modernist, introduces the immersive first gallery and provides audio descriptions for a selection of paintings in this exhibition.

Screenshot of the Audio Description app for Rita Angus: New Zealand Modernist

Rita Angus: New Zealand Modernist was open at Te Papa from 18 Dec 2021 – 25 Apr 2022.

This audio descriptive introduction introduces the immersive first gallery and provides audio descriptions for a selection of paintings in the exhibition.

There are four tracks in total, one for each of the four galleries, with a transcript for each.

You can also access the tracks and transcripts in a format that includes images of the paintings and is optimised for blind and low vision users, here: tepapa.nz/adrita

The four tracks are:

This track has a gallery introduction and audio descriptions for the paintings: Self-portrait, 1929, Cleopatra, 1938, Fay and Jane Birkinshaw, 1938, Marjorie Marshall, 1938-39/1943, Landscape Wanaka 1939, Cass, 1936

This track has a gallery introduction and audio descriptions for the paintings: Self-portrait, 1947, Tree, 1943, Douglas Lilburn, 1945, Self-portrait, 1943, Rutu, 1941

This track has a gallery introduction and audio descriptions for the paintings: Self-portrait, 1967-68, Central Otago, 1943-36/1969, Scrub burning, northern Hawkes Bay, 1965, Flight, 1969

Jump to:

Introduction

Kia ora. I’m Judith Jones, an audio describer at Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

Welcome to this audio descriptive introduction to Rita Angus: New Zealand Modernist. There are four tracks. This first one introduces the exhibition and its immersive opening gallery. The next three tracks offer audio descriptions of some works in three smaller galleries, which follow a chronological journey through Rita’s life and work.

From the 1930s onwards, Rita Angus boldly forged a life as an artist. Her ground-breaking works express her feminism and pacifism, and her identity as a 20th-century woman painter. This exhibition brings together more than 70 of her works – from Te Papa’s art collection, the Rita Angus loan collection, and other public and private collections.

It’s all there, the strangeness, colour, exhilaration.

Rita Angus

Rita saw colour as a powerful way of communicating – almost a language. Colour surrounds us as we begin our experience with the vibrant world of her work. We’re in a huge, two-storey space. The floor and walls are white. Coloured fabric banners, 1.4 metres wide, drape here and there from the ceiling above, falling to different lengths. They’re not attached to the floor and will move as visitors pass by.

A bridge runs through this gallery, 4 metres above us and 3 metres wide, taking people across Level 5.

The soundscape from a short film projected on the walls on either side of us threads through the space. We’ll hear orchestral music and the sounds of nature.

The film, A Painter’s Journey, takes us into the spectacular world of Rita’s oil painting Central Otago. Each screen is the length of the 13-metre-wide wall, and 7 metres high. The film is around 10 minutes long and plays on a continuous loop. There are bench seats nearby for visitors to sit on.

The banners in this gallery pick up the colours Rita used for the tones of water, sky, earth, and rocks in her watercolour studies for this painting.

The landscape Central Otago is one of Rita’s most important paintings, and is audio described in Track 4, ‘A world of colour’ gallery.

A Painter’s Journey

I’ve tried through the medium of paint to express … how simple and wonderful living is …

Rita Angus, 1944

This short film, made by Te Papa, celebrates Rita’s artistic practice – diving into her painting Central Otago. Central Otago has colour and vitality that capture Rita’s deep feeling for and close observation of this wild, dramatic landscape.

She spent two weeks travelling through the area in the summer of 1953, recording what she saw, what she experienced, in watercolour studies and sketches. She then pieced these together to create a single oil painting.

Rita captured the multiple landscapes, light, moods, movement, and textures of an entire region in one composite picture, from the high alps to a lake with the wind ruffling its waters, the foothills and farmlands, mounds of earth left by gold dredges, farm buildings, and the tiny wooden church at Naseby.

She painted Central Otago through 1953 to 1956 and reworked the painting in 1969. In this film, we imagine her process. Explore the landscapes Rita captures in paint, and her vivid palette of colour. Trace the evolution of the work – from fluid watercolour study to crisp oil painting.

A Painter’s Journey takes us on an immersive journey into the rich, vivid details of the work and the artist’s practice. The soundscape includes Douglas Lilburn’s work Four Canzonas for String Orchestra) and natural sounds recorded in Central Otago in 2021.

I asked the filmmaker, Prue Donald, Te Papa’s Digital Producer, to tell us about her journey making this film.

Prue Donald

Following Rita’s travels, we ventured south to Central Otago in October 2021, armed with copies of her watercolours, stopping to seek local knowledge about where a particular bend in the river might be. Some landscapes she captured in a few sharply observed lines, but enough for locals to recognise the shape of a ridge.

Rita travelled through Central by bus, so she would have explored these places on foot – we know she was a great walker. We imagined her arriving, say, in Arrowtown, maybe heading for a friend’s crib to stay a few nights, and finding a nearby lookout point to sketch landscapes in detail. We’re certain she would have climbed Tobins Track, for instance, to get a spectacular panorama of the Wakatipu basin – which maybe inspired her bird’s-eye view of the region that you sense in the oil painting.

At the places that drew her attention, we heard the wind through the tussocks on the barren hills, the chorus of birds in the still morning air, the sound of water rushing through shallow riverbeds – and imagined Rita might have experienced the same sense of thrilling isolation, of being in the world of the wild back country, feeling the deep momentum at the banks of the Clutha River, or admiring the simplicity of a tiny wooden church in the forest. And picking up her brushes to paint.

Moving into the next three galleries

As we leave this first gallery, we’ll pass the staircase to Level 5 on our left. From here, as we move ahead, there’s an art activity studio on the right. Visitors can take a seat and relax here, or explore colour and portrait-making with hands-on activities. When we have travelled through the three next galleries, we will come to the other end of this space. As we move forwards towards the first of three connected galleries, we will travel around either side of a layered set of green banners that signals the entry into the main exhibition area.

The three galleries display works in oil and watercolour, covering the full 40 years of Rita Angus’s practice as an artist.

She was born in Hastings in 1908 and died in Wellington in 1970. Te Papa houses the largest collection of Rita’s work, made up from artworks in Te Papa’s own collection, and over 700 oil paintings, watercolours, sketches, and works on paper from the Rita Angus loan collection. The loan collection has been held by Te Papa, on behalf of the estate, since the artist’s death.

Rita used two names for her signature over time. She changed her name to Rita Cook when she married the artist Alfred Cook in 1930. They separated in 1934 and divorced in 1939. In 1947, she changed her signature back to Rita Angus.

The next galleries are all standard roof height, their walls are painted white, and the floors are concrete. There will be some seating available in each. There are some banners within these gallery spaces. Their banner colours align to those of artworks within each.

The following three recorded tracks are named for each gallery. I’ll introduce their themes and audio describe some works in each. There’ll be a brief sound interlude after each audio description.

I have been able to devote my energies to what I really am, a woman painter. It is my life.

Rita Angus

Feminist, political, unconventional. Rita’s work grappled with what it meant to be a New Zealander, a modern woman, and an artist. The 1920s and 1930s were a time of social upheaval and change – she responded fearlessly to this new age in both her life and work.

In this gallery, we see Rita establishing herself as an artist, and developing her distinctive, graphic style of oil painting. She painted and drew herself constantly – self-portraits are important in her practice.

Rita was a third-generation New Zealander of Scots–English descent, fair-skinned with grey-brown eyes. Her friend Betty Curnow said, ‘She had lovely wavy golden hair in the ’forties, worn long, down on her shoulders. In Wellington as it grew whiter she had it cut shorter each time I visited: but each style always seemed just right for her face.’

Rita’s honest self-portraits often emphasise the lines of her facial features, her prominent nose and cheekbones, the cleft in her chin and the philtrum – the indentation above the top lip – in an almost sculptural way.

I’ll begin by describing the first self-portrait she exhibited.

Self-portrait, 1929

This oil painting on canvas is 38cm wide by 47cm high. It’s on loan to Te Papa from the Rita Angus Estate.

Rita painted this when she was 21 years old, a third-year art student in Christchurch.

It’s a three-quarter-length work. She stands with her left shoulder nearer us and her head turned our way. The background is a light brown. The paint has slightly cracked on the canvas over time.

She’s casually clad in her artist’s working clothes, and gazes out with quiet confidence. Her mouth is closed, lips warmed with soft red colour.

Her orange beret is a splash of bright colour. The beret’s thin little stalk sticks jauntily upwards.

Her hair has been tucked up inside the beret at the back, and at the front held clear of her fair-skinned forehead. Some blonde curls escape alongside her ears.

She wears an open, blue, long-sleeved working shirt with a soft collar. Rita uses blue tones with whiter patches to capture the light along her left side and show the loose form of the shirt as it drapes around her. Underneath she wears a green, round-necked top.

There is a forthright independence to this portrait of herself as an artist, which captures something of what makes Rita distinctively modern, and a woman of her age.

Cleopatra

is an oil painting on canvas, painted in 1938. It’s part of Te Papa’s art collection. It’s 38cm wide and 46cm high.

Rita once wrote that she had been born at the time the Egyptian tombs were opened. She was fascinated by the ancient Egyptian civilisation, and intrigued by Cleopatra specifically as a woman wielding power.

In this three-quarter-length portrait, painted when she was 30 years old, Rita is a Cleopatra for the modern age. She takes the Egyptian queen’s name, and theatrically positions herself as if she is a flat figure on an Egyptian mural. Her body is almost front-on to us, but her head is in profile, facing to her right.

Rather than painting herself exactly as we would see her in person, this portrait is very crisp and sharp. Rita’s figure is flat, almost outlined, with distinctive clear colours. This is a very modern style of portrait – it feels fresh and powerful.

The background is a bright, fresh green, showing something of the texture of the canvas.

Rita glances our way with a somewhat quizzical, amused expression. Her eye looks both out at us and straight ahead. Her mouth is closed, darkened by bold red lipstick, and emphasised by a slight shimmer of lighter green in the background close by.

In another nod to the classical Egyptian pose, her right arm bends up at the elbow and back at the wrist, holding her hand out towards the edge of the frame, palm upwards. Her little finger and one other curve back in over her palm, but that’s all. The others are cropped off at the edge of the canvas. Our Te Papa conservators noted the paint in this area, usually so smooth in Rita’s oil paintings, looked a bit rougher. They examined the painting under infrared light and saw her initial drawing in charcoal or pencil, in which Rita’s hand seems to be holding a smoking cigarette. The artist had painted this part over.

Rita’s browny hair hangs to neck length. Paint in darker and lighter tones shapes and sculpts its wavy texture. One curl flicks high over her fair forehead to her left brow. A narrow, lighter green glow in the background sweeps around and accentuates the shape of her head and the colours in her hair.

She wears a pale green, sleeveless dress that’s cut sharply back from the underarm to the high collar line. The crescent curves of her bare shoulders stand out against the background, and darker skin tones create light shadows that highlight her clavicles.

The collar falls in long, thin triangles. It’s fastened with one of three large white buttons, evenly spaced down the front of the dress.

Fay and Jane Birkinshaw

is an oil painting on canvas, painted in 1938. It’s part of Te Papa’s art collection. It’s 69cm wide and 53cm high.

The two girls of the title – young, fair-skinned, bright-eyed, and fresh-faced, hair off their foreheads – sit side by side, elbows almost touching, against plumped blue cushions on a high-backed cane sofa.

Fay, who’s around 7 years old, on our left, has blue eyes and short, bouncy fair hair, tied with a thin red ribbon high across her brow. Jane, about 9, has brown eyes and short, straight brown hair, tied in the same way with a green ribbon.

A pale flush lights the sisters’ faces, as if someone has given them a quick dab with a warm facecloth. Their closed mouths are smiling enough to dimple their cheeks.

The sisters wear identical red and white checked dresses, with wide, soft, curved white collars. Their skirts flare out across their laps and the sofa – there’s no line to show where one starts and the other ends between them.

Each wears a green cardigan. These are really similar, though not exactly the same in shade or style.

Together, the girls support an open book across their laps, each holding it with her outer hand. Most of the book is out of frame, but there’s a bit of a picture low on one page.

Three dolls are displayed on a shelf up behind the sofa – evenly spaced, one seated at either side, and one standing between the girls’ heads. They’re all quite different. Rita dressed and draped them in dolls’ clothes and material.

The doll to the left seems to be a hard plastic. Her arms and a foot that sticks out under her skirt reach forward in a fixed position. She has black skin, and white dots for eyes. There’s a piece of blue material over her head, tied in a bow below her chin, and she wears a white apron over a red dress.

The middle doll is standing. Its head could be porcelain – it’s very white, its features and edges uneven, maybe chipped. Seams on the arms reveal its body as fabric. It’s got wide eyes with something of a surprised expression. A yellow, flat hat lies angled over the top of its head, with black and red detail at the centre. A piece of blue material draped across its shoulders is held in place at the front by a long silver pin. Its lower clothing is green.

The doll to the right is sitting. Her brown skin is fabric. Her bare arms stick out from her sides. She wears a tight blue cap with red tassel trim, a blue and white top, and green and red lower clothes. Her red shoes stick out towards us.

Arranged at the top of the painting, a few pieces of a green tea set seem to hover in the air against a light-brown wall. There’s an angular-style jug at each side, and two cups and a plate holding a layered iced biscuit float across the centre.

Marjorie Marshall

is an oil painting on canvas. It’s part of Te Papa’s art collection. It’s 48cm wide and 56cm high.

This is a mid-length portrait of a friend of Rita’s, who she met at art school. The portrait is set in Central Otago, near Lake Wānaka, where Rita and Marjorie sketched together. It was painted over two years when Marjorie was in her late 20s – in 1938 and 1939 – and then parts of it were repainted in 1943.

The painting combines the two main strands of Rita’s work – portraiture and landscape – with particular boldness and intensity. It has a warmth of colour and tone that reflects Rita’s affection for her two subjects: her friend and the landscape.

Marjorie, with fair skin and brown hair, stands in the centre of the frame. Her body is almost full-on to us, her head is slightly turned to her right, and her bright brown eyes look away in that direction as if she’s seen something interesting. She’s smiling – her lips turn up though her mouth is closed.

A soft yellow scarf with thick fringes sticking out along its sides, almost with a life of their own, drapes over her head and ties in a wide knot under her chin. She wears a tailored green jacket. Underneath there’s a richly warm-orange top, almost blazing in the centre of the painting. Marjorie’s warm clothes, the brightness of the colours, and the jaunty angle of her scarf suggest that a stiff spring wind might be blowing through the valley where she stands.

The landscape that frames her stretches from narrow strips of tilled field at the bottom of the work, across bare land with bare trees, to a line of low hills and two sets of higher ranges.

At the top of the painting, the artist signalling their distance with shades of soft blue, the angular shapes of bare, rocky mountain peaks stand against the blue sky with high, scudding clouds. It’s hard to tell where the mountains end and the sky begins.

In front of these, a line of ranges in a rich brown, with dark shadows outlining their steep faces, stands strong and sharp in a triangular block behind Marjorie’s scarf-wrapped head. Softer, lighter brown hills curve across in front of these on the far side of icy blue water, which crosses the painting just below halfway, its lightness framing the line of her shoulders. The shoreline, on her side of it, is fenced off with a line of battens and wire.

On either side of Marjorie, a tree grows from the brown earth and stretches out bare branches.

Landscape (Wanaka)

is a watercolour on paper, painted in 1939. It’s part of Te Papa’s art collection. This work is 28cm wide by 23cm high.

The artist shows her accomplished control of the delicate medium of watercolour to create both clearly defined lines and forms with vivid colour, and softer shapes washed with gentler shades.

A field of low green plants, scattered with white flowers, fills the bottom half of the painting. From midway, there is pasture, then low hills, then a valley cuts through angled planes of mountainsides towards one distant central peak, beneath a pale sky.

The plants would be about ankle height should we wander through. Rita brings this foreground foliage to life with precise flicks of paint in vivid greens, leaving some of the unpainted white paper to shine through. The luminous field seems to be almost rippling in an unseen breeze.

Perhaps that’s what has darkened the waters of a small pond or large puddle in the front centre. Rita streaks black lines across the surface, as if it’s rippling or reflecting a chill sky. It feels like it would be cold if you walked through it.

A thin, light-brown line traverses the centre of the picture, as the ground starts to rise to a low green hillside. The artist marks straight, tiny, silhouetted battens of a fence line that march along the top of the hill. They’re not the only indications of people in this place – beyond the fence, there’s a stretch of ploughed land on the left, and low golden hillsides have swathes cut across them, as if crops are being harvested. On top of another hill to the right, there’s a stand of dark trees near two blocky farm buildings – tiny rectangular forms, straight-edged like the fence line.

Rita works with the flowing wateriness of watercolour, with soft-washed changes in colour and tone, to signal the distance and forms of the hills as they give way to the mountains across the top half of the painting. A low purple ridge reaches right across the frame behind the golden hills, with a few tiny trees along its heights.

Beyond this, the land divides into a valley, set between mountains that loom as high triangles on either side, soft in colour but firm in form against the sky. Away in the central distance, a rounded blue peak stands sentinel and alone.

Cass

is an oil on canvas painting, on loan from Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. It’s 37cm wide by 46cm high.

A little, red, boxy, weatherboard railway station stands on a platform in the middle of the painting. It’s barely a station – more of a shed. It stands, almost waits, while shadows are cast across it, in the centre of a powerful Canterbury high country landscape. There’s tussock in the foreground, rumpled hills and towering mountain peaks across the back. White clouds scudding across the sky show the air is on the move above.

‘Cass’, announces a small sign on the front of the little building. And ‘Cass’, says another small sign on the station’s right wall.

Rita painted Cass in 1936, after she’d caught the train to the remote rural area with some friends to find things to sketch and paint.

The station building sits on a concrete platform running across the lower third of the canvas. It has one open door facing us, and one that’s shut. A man sits alone on the platform to our right, wearing a heavy coat and a hat and smoking a pipe.

To our left at the end of the platform, there’s the open side of a large corrugated iron shed, and to the right, there’s one end of a red freight car.

Sandy tussock spikes up across the foreground, growing untamed over bumpy ground. In front of the station, there’s an irregular pile of cut planks. Poet Denis Glover, writing about Cass in the late 1970s, said, ‘Rita saw it with utter directness … though the stack of timber looks like a batch of bad cheese-straw.’

A row of trees forms a dark triangle behind the station, the tallest ones at its peak. Through these to the left, there’s part of a farm building, in farm building red with a black roof. It sits at the base of rounded hills, two sets of which lie like lumpy duvets, softly coloured in warm reds and browns. Rita builds on the geometry of the triangular trees, forming these rolling hillsides as soft triangles too, their wider edges by each side of the frame angling down towards the centre as the trees grow up from it.

Behind them, the imposing flanks of higher mountains form the same angled shapes in from the edges of the painting, those on the right darkened purple with shadow.

Above the V-shaped valley between the mountains, and over the line of their slopes, white clouds seem almost to dance

I have never lost my faith in my painting, my work, as a child or an adult, in sickness or health, success or failure, peace or war …

Rita Angus

Rita was a committed pacifist, actively opposed to World War II (1939–45). She believed her art could help construct a peaceful future, and took inspiration from music, nature, family, and friends.

Self-portrait, 1947

is a watercolour on paper. It’s on loan to Te Papa from the Rita Angus Estate. It’s 24cm wide by 29cm high.

This half-length portrait, painted when Rita was 39, has an open simplicity to it. The artist is entirely and intentionally the focus and substance of the painting. She offers herself as the primary sense and feel of the work. She presents herself honestly, as if for us to study, as if she has closely studied herself to capture her features and expression with such precision.

Rita fills most of the frame, placing herself against a neutral yet softly textured background. She wears a plain, blue, round-necked jumper, with a hint of soft texture to it, as if it’s been worn and worn and washed, and the wool fibres have softened.

Her dark-blonde hair is parted firmly in the middle, and a straight hairclip holds her curls high off her forehead on her right, with another out of view holding it up on her left. It falls loose in tumbling, almost touchable soft curls to her shoulders.

Her forehead is creased across with light-red lines and vertical ones that rise between her eyebrows, which sweep in a dark curve above her brown eyes. Her cheekbones and long nose are shaded to hold their distinctive forms. Her skin is fair but warm. Rita often used surprising colours. Here, she’s used a pale green to create shadows that highlight the contours of her face.

This is one of the first works where the artist signs her name Rita Angus again, instead of her married name, Rita Cook, which she’d used since 1932. She’d divorced in 1939.

This painting was featured in the 1947 Year Book of the Arts in New Zealand. In her artist’s statement, Rita wrote ‘as a woman painter’ and said, ‘I endeavour to record the alive, constructive and courteous spirit of the age’.

Tree

This watercolour on paper is 28cm wide by 25cm high. It’s part of Te Papa’s art collection.

A lone, leafless tree stands, almost seems to float, in the centre of the painting. Rita sketched for this work in Greymouth, where she was staying alone in the spring of 1943. There was a cherry tree in the front garden.

The tree emerges, just seems to appear, growing up from a featureless beige foreground that takes up the lower third of the work.

The tree’s smooth brown trunk curves a little to the left then realigns as it stretches up in front of low and softly formed, distant blue hills – as if it’s been growing here a while and shaped its growth to something that happened here seasons ago.

Branches extend from the top of the trunk, thinning and forking as they spread across the paper. The delicate yet somehow energetic, stark lines of smaller twigs cascade out and down, the whole forming a shape like a huge, irregular, line-filled umbrella.

Little buds of spring growth stud the criss-crossing lines, all tiny but standing out in silhouette against the pale sky like beads threaded along a string.

Three small, dark birds perch high in the tree, all facing different ways, as if they’re about to hop about or take flight or sing.

Douglas Lilburn

This three-quarter-length portrait is watercolour on paper, 34cm wide by 44cm high. It’s on loan to Te Papa from the Rita Angus Estate.

It was painted in 1945. Rita met composer and musician Douglas Lilburn in 1941. They developed a brief romantic relationship, followed by an enduring friendship. Rita would often write to him about the connections between his work as a composer and her paintings. She talked about the colours of the painting as being linked to the music he was creating.

Rita wrote to Douglas that this was ‘an intimate portrait’. It is delicate in colour and line, with an overall sense of softness and affection. She’s painted him as if he’s right next to her, to us. Away in the distance, there’s a scene familiar to both of them: the coastline below her cottage on Clifton Hill in Christchurch. It is a bright, still, lightly cloudy day.

Douglas was 30 years old when Rita painted him. He looks away to his right, a steady, thoughtful gaze from pale eyes. He has short, fair hair with a tumble of soft curls high across his fair-skinned forehead. Thin, white vertical lines on the rounded lenses of his plain framed glasses indicate glints of sunlight. Rita uses pale, soft whites to show how light falls on the right side of his face, and warmer tones on the other. He’s wearing an open-necked, casual white shirt. Soft blues and yellows outline its form and folds.

Behind Douglas, the softly paint-washed sky takes up the top quarter of the paper. It meets the sea below along a deep-purple horizon. There’s a curve of tussocky beach to our left. The sea splashes lightly blue onto the sandy shore.

Self-portrait (with moth and caterpillar)

This three-quarter pencil and watercolour portrait on paper is a work in progress, started in 1943 when Rita was 35 but never completed. It’s 25cm wide by 35cm high, on loan to Te Papa from the Rita Angus Estate.

Rita stands on the sandy beach at Clifton in Christchurch. The sea curves in from the right and away behind her to the far hills.

Paint’s only been applied so far to the upper half of the paper, and then not to everything. For the rest of the work, we must decipher her intent from the light pencil strokes that outline some basic forms, like the rest of her body as she faces us with her arms by her sides.

She has painted the pale sky with a low bank of white clouds across the top, and the distant hills with low mist, or perhaps smoke, rising from the valleys.

She has painted her head, neck, and the pale blue collar of a shirt that’s underneath her jumper. Her fully painted face holds a powerful presence, vivid against the soft colours of the sky, the white of the paper, and the sketchy pencil marks.

Her golden hair is held off her fair-skinned forehead with a clip high on each side. She looks steadily away to her right – a contemplative gaze, perhaps slightly downcast. Many of her friends remarked on how accurate the portrait was.

Her jumper is still an outline, with a rounded-petal flower sketched on the front. But there are two splashes of colour on her right shoulder. A green caterpillar crawls along on two sets of tiny feet. Lower, a moth lies with four pinky-red outstretched wings, but its probing antennae still just pencilled in. The gentle pencil outline of a short, sinuous snake moves up her left shoulder.

Further down the shore, beyond Rita’s left shoulder, there’s a figure of a young woman facing us. Rita had begun to paint her. She has brown hair, brown eyes, and brown skin, and a top and skirt in brown and purple. Her bare legs and feet are just drawn in pencil. So are her arms, with one hand holding the top of the long handle of a spade.

Other than a small section of water where it meets the sand behind Rita’s shoulder, the rest of the sea and the shore remain blank paper still – except for a few faint marks pencilling indistinct shapes on the sand.

Rutu

This is an oil painting on canvas, 56cm wide by 71cm high. It’s part of Te Papa’s art collection. Planned and painted over about five years, it was finished in 1951.

This is one of Rita’s three goddess works, which bring life to her vision for a pacifist, multicultural future in New Zealand. She believed these three goddesses to be among the major works of her lifetime and often described Rutu as her child.

Rutu is a painting of a woman in a coastal Pacific setting. She sits at ease on a chair, surrounded by lush foliage, on a rise with her back to the ocean. Behind her shoulders, the light-blue sky meets the dark-blue sea along a featureless horizon. A large, deep-yellow circle with a strong, dark outline – the sun, or a halo perhaps – frames her head against the sky. She’s almost life-size. Her body turns a little to her right. She cradles a waterlily just above her lap where the painting ends.

Although the figure in Rutu does look like Rita, in her letters to her friend Douglas Lilburn, she wrote that she thought about the painting as an imaginary portrait rather than a self-portrait.

Rutu, this woman of Rita’s imagination, has smooth, quite dark-brown skin, and strikingly – almost artificially bright – yellow hair. It sits high above her forehead and falls in long, wide strands over her shoulders, where it spreads out. Unlike her other portraits, it doesn’t have the texture of hair. It falls instead as flat lengths – almost like cut-out fabric.

She seems serene. Perhaps it is her steady gaze from blue-grey eyes, looking out to her right, and her gently closed mouth. She wears a red, close-fitting, short-sleeved top. It has a deep scoop neck trimmed with a dark panel decorated with three little golden fish swimming across it to our left. The top is tucked into the waistband of a rich blue-purple skirt.

The tips of her long, fine index fingers, and thumbs behind, gently hold the outer petals of a large, creamy-white waterlily flower above her lap, with its long, green stem stretching below.

Lines of white, curling breakers meet the shore behind her shoulders. From here on either side, there’s a line of spiky vegetation, then tall palm trees. Red-leafed shrubs frame either side of the seat she’s on. She sits up straight but at ease on a wide wooden chair painted with red and black stripes, and brown rounded shapes.

I am still trying to express … the vast variations & endless possibilities in paint.

Rita Angus

In her 50s and 60s, Rita continued to experiment with new ways of painting. She was alive to the world around her – capturing its colour and detail, revealing its strangeness and intensity.

Self-portrait, 1967–1968

This is a three-quarter-length portrait, oil on board, 40cm wide by 58cm high. It’s on loan from a private collection.

The artist faces us, dressed warmly, against sculpted trees and a chill grey sky. This is the last completed self-portrait of Rita Angus, painted in oils over two years as she was turning 60, and completed two years before she died. She wrote in her diary: ‘I was trying to paint age into it.’

A close-fitting black hat is set firmly on her head, its form dense and dark against the sky. It covers most of her short, grey hair.

Rita’s brown eyes look directly and steadily out of the painting. There’s a warm tone to her skin, and a calm air in her gaze towards us. Dark shades trace deepening creases, etching age between her brows, around her mouth and eyes, and puckering lightly across her neck.

Rita wears a red jacket warm in tone, and it seems like it would keep her warm too, with a curved-neck pink top showing between its angled lapels.

Behind her the trees, their foliage formed by green shapes that run into each other, grow up on solid trunks, up towards a pale, cloudless sky.

A single, leafless brown tree limb curves in from high on the right edge of the frame. At first it echoes the line of her left shoulder. It arcs over and past the top of her black hat, then branches out as stark lines against the clear sky above her.

Central Otago

This is an oil on canvas painting, 63cm wide by 52cm high. It’s part of Te Papa’s art collection.

Central Otago is a vibrant, detailed painting that layers together multiple landscapes and different perspectives to create a wide, sweeping panorama of the region, as if we can experience everything, everywhere at once.

It all spreads out before us, from the high, craggy alps under a cloudy sky, to the eroded hillsides and gentler foothills, and wide, cultivated land scattered with a few trees and buildings. The myriad forms, lines, and textures of the land are bathed in a golden light, as if Rita has washed summer sunlight across the scene.

As she began this work, Rita wrote to her friend Douglas Lilburn, ‘It’s all there, the strangeness, colour, exhilaration.’ He’d supported her to take a sketching tour through the area in the summer of 1953. She recorded the journey in pencil notes, and detailed watercolour studies and sketches.

Central Otago is almost like a painted journal of the experiences and sensations Rita absorbed through that time. She worked on it through 1953 to 1956, and again off and on until 1969, the year before she died.

Rita settles the finely observed and delicately captured landscapes of her watercolour studies, sometimes almost unchanged, within a whole new landscape, capturing the spirit of the land, the movement of weather and light and wind.

The painting is made up of multiple layers of landscape. The lower part of the work is a complete landscape in itself, almost a painting within a painting. It starts with a green hill that gives way to the flat bed of a valley surrounded by several retreating lines of lumpy hills. To the left, the little wooden church from Naseby stands tall on a plateau. Where we would expect skyline along the top of the view, above the distant hills, it blends instead into another landscape above it.

Through the middle plane of the work, there’s a softness of gently rolling open land, a small, rugged rock formation sitting solid in its centre. This central area is almost luminous with golden red colour. There’s evidence of cultivation, and tiny houses are scattered within this central zone. To the left, mounds of earth dredged by gold diggers lie across the land like miniature versions of a higher, naturally mounded hill beside them. To the right sit some small, blocky, windowless farm buildings. There’s a line of trees at the very edge, with a faint outline of buildings behind them. Perhaps this is one of Arrowtown’s tree-lined streets.

The top of the painting takes us slowly up into the high country. There’s a sculptural nature to the painted contours and outlines of these lands – the hills, raw-sided and soft-sided, covered in grass or scrub or tussock, and the craggy, sweeping faces of the mountains. A chilled lake lies in a valley towards top left. The wind is whipping up white-capped waves, and blustering through a few green trees on the shoreline.

This scene, with the mountain flanks behind the water, is lifted almost exactly from a watercolour study. When she painted the watercolour, Rita would have been close to the trees, so they are quite big compared to the mountains away behind them. She’s kept that proportion in the oil painting, so these moving trees loom large here, their branches almost reaching out of the vast landscape and into the sky.

The painting combines Rita’s views, experiences, and memories of different parts of Central Otago. It is a portrait of a place, not an exact single view or a geological replica of the area.

Douglas Lilburn donated the painting and the studies to the National Art Gallery (now Te Papa) in 1972, saying, ‘so that the record of her journey and her vision would be preserved intact’.

Scrub burning, northern Hawke’s Bay

This oil on board painting is on loan from Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. It’s a square, around 60cm by 60cm.

Rita painted this in 1965, after visiting her nephew’s family in Hawke’s Bay and watching him light a fire to burn off scrub, to clear the land for farming. There are no flames in the painting and no burning scrub. The fire is in a valley between richly dark-green, textured, bush-clad hills. There are no people either – no one travels the curves of a road that shows through the trees on the right.

But there is smoke. Smoke curves, curls, and billows, and holds the whole centre of the work. It rises in a column that starts low on the far left edge, from behind a green, grassy hillside. There’s a tiny blocky shape on that hillside, maybe a hut, the only thing with straight lines in the whole work. It casts a tiny shadow from sunlight over to our right. Sunlight clear of the smoke, shining on and through it, gives it a radiant glow.

The smoke swirls and expands as the fire – moving across to the right behind the bushy hills – seemingly eats up everything in its path. Sculptural forms of red and grey smoke tumble and surge high over the landscape, blotting out the sky, then turn back on themselves as if the wind direction is different higher up. Above the hot haze of the dense smoke, there are a few puffy white clouds in the loomy dark sky.

If you were standing nearby, it might feel as if the world was on fire, the heat singeing and sucking at the air itself, while the ash caught in the smoke would fall across burned and unburned land alike.

Flight

This oil painting, painted in 1969, would be Rita’s last oil painting. It’s part of Te Papa’s art collection. It’s 61cm wide by 60cm high.

A graveyard monument dove is mid flight above a coastal bay, where tombstones lie seemingly abandoned on the shore on a bright, sunny day. The dark-blue waters are framed by a hilly headland that juts into the ocean, leaving a brief stretch of horizon line on the left, and craggy rocks and a grassy strip in the foreground. A bank of white clouds moves in from the sea towards the highest edge of the headland. To the right, grey smoke billows up from a valley, rising as a twisting column into the sky.

Three small, white fishing boats lie at anchor in the bay, facing out to the sea. The water is so still that sunlight on each casts a light reflection on the water. Another fishing boat chugs in from the open ocean, breaking a line of white caps in its wake, while someone in wet weather gear stands sentinel in the bow.

A few sharp brown rocks break the waters close by shore, outliers from the rocky coastline that takes up about the lower third of the painting. A lone red-billed, red-legged seagull perches on its chosen rock above a small, placid pool to the right.

On the grassy foreshore, there’s a roughly formed pile of tombstones – perhaps 20. Two upright crosses stand amongst them. The others are solid shapes, hewn from concrete and marble, worn and weathered, most rectangles with angled or curved tops. Some stand upright while others lie cast or stacked sideways. None have inscriptions on the sides that face us.

Above the bay, the huge stone dove holds steady in the air, its beak to our left, its head against the clouds, its large feet angled forward as if to land. The dove is in flight, wings spread, but there’s a sense of heaviness about it. It’s coloured like the grey gravestones, as if it too has been wrenched from a cemetery. Its beak holds the stalk of a wide, drooping piece of foliage, or perhaps a drift of fabric, also sculpted in solid stone.

The audio description of Flight, Rita’s last oil painting, was the last track in this introduction to the Rita Angus: New Zealand Modernist exhibition.

From the end of this gallery, you can walk through the art activity studio to the central space near the staircase.

The exhibition will be open at Te Papa until 25 April 2022.

You can find out more about Te Papa’s art collection on the Te Papa website, and search Collections Online for particular works.

Thank you for listening.

Rita Angus created a distinctive vision of a new, modern New Zealand. This landmark exhibition celebrates 40 years of her work.

Closed

18 Dec 2021 – 25 Apr 2022

Exhibition Ngā whakaaturanga

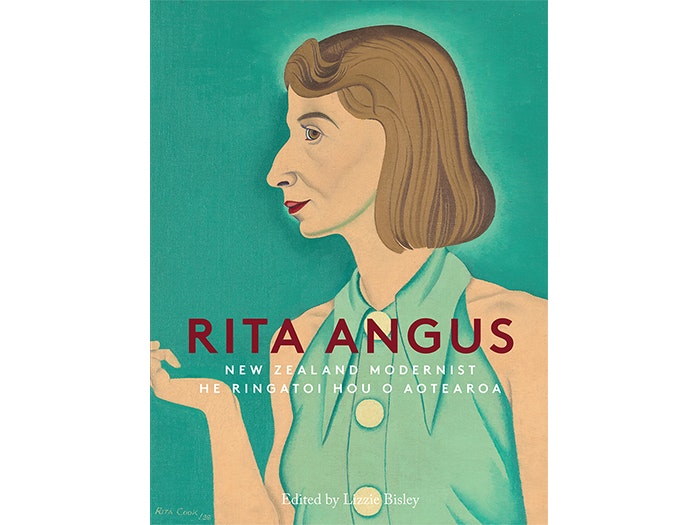

The companion catalogue to the major Rita Angus show at Te Papa.

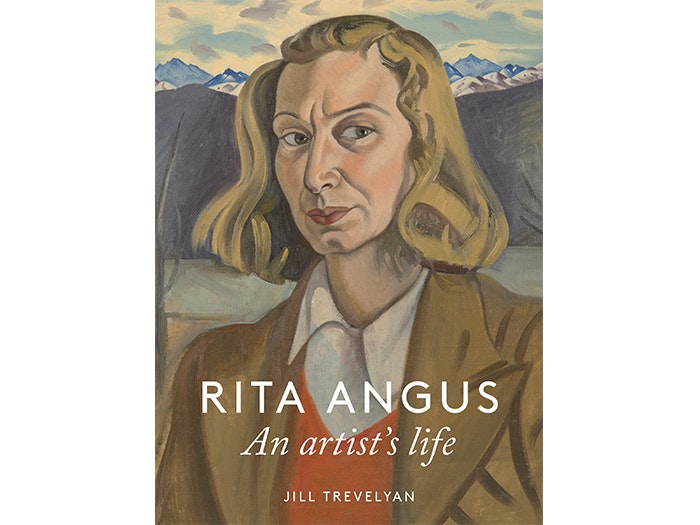

Revised edition of the award-winning biography of one of New Zealand's most famous women artists.