Wanwan Liao’s story

“I felt like I had a superpower with my Hakka. It meant that I had a special language that others couldn’t understand.”

Wanwan Liao talks about her relationship with Hakka, Mandarin, and Taiwanese Hokkien.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

“I felt like I had a superpower with my Hakka. It meant that I had a special language that others couldn’t understand.”

Wanwan Liao talks about her relationship with Hakka, Mandarin, and Taiwanese Hokkien.

Click the expansion arrows to open this slideshow in full-window view.

Choosing to tell Wanwan’s story came naturally for me: we were both Taiwanese, both Newtown residents, and her passion for bilingualism in the classroom was fascinating to encounter.

We bonded over our connection with Hakka/Mandarin, racism in schooling systems, diasporic guilt, and our fading mother tongues. As much as I helped bring Wanwan’s story to life in pictures, her passion, commitment, and vision was also a source of inner healing for me.

I have hope for future migrant and bilingual children in Aotearoa, knowing that there are mentors like Wanwan leading the way.

– Ronia Ibrahim

“I felt like I had a superpower with my Hakka. It meant that I had a special language that others couldn’t understand.”

Wanwan Liao talks about her relationship with Hakka, Mandarin, and Taiwanese Hokkien.

“[Buying a balloon] was such a simple and playful act, but it reminds me of the wholesome joys that connecting with your culture can bring.”

Koreen Liew-Young talks about her long-gestating relationship with Cantonese and Mandarin.

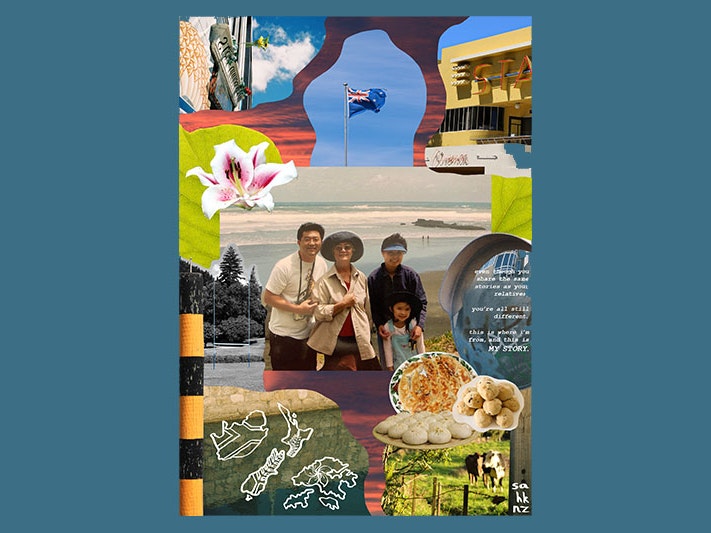

“I think telling diasporic stories, like mine, bring alternative and often undocumented/heavily underrepresented experiences to light.”

Samantha Fei talks about her relationship with Cantonese, which begins in apartheid South Africa.