Tuhinga 25, 2014

Full Tuhinga issue 25 (2.47 MB)

or download the individual article you’re interested in below.

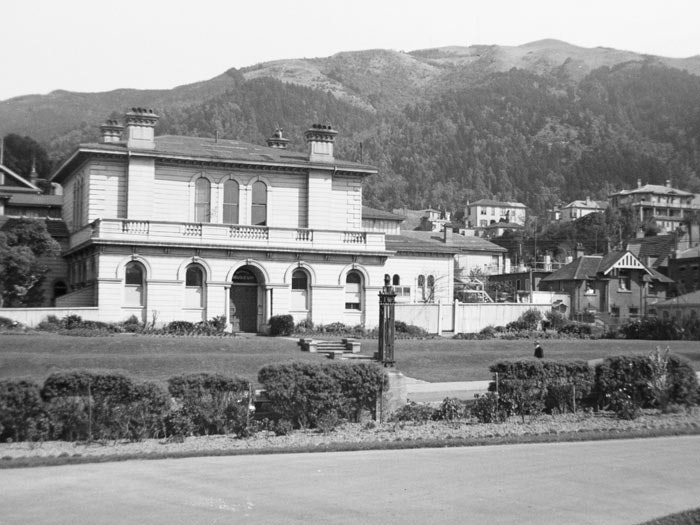

Domestic expenditure of the Hector family in the early 1870s examines the Hector family accounts from the early 1870s. The accounts give an insight into the lifestyle of James and Georgiana Hector when they lived in Museum House, next door to the Colonial Museum in Wellington. James Hector was director of the Geological Survey and Colonial Museum.

Go to Domestic expenditure of the Hector family in the early 1870s

Ko Tītokowaru: te poupou rangatira Tītokowaru: a carved panel of the Taranaki leader examines and documents the history of a carved poupou (panel) depicting Taranaki rangatira (chief) Tītokowaru. The poupou was purchased for the Colonial Museum (now the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa) by Augustus Hamilton, director of the Museum, in 1905 and was loaned to the Department of External Affairs around 1953 for display at the newly opened New Zealand Embassy in Paris, France. Research in 2012 revealed its whereabouts and ensuing discussions allowed its return to Te Papa.

Go to Ko Tītokowaru: te poupou rangatira Tītokowaru: a carved panel of the Taranaki leader

Legal protection of New Zealand’s indigenous terrestrial fauna – an historical review explores New Zealand’s complex history of wildlife protection. At least 609 different pieces of legislation affecting the protection of native wildlife were passed between 1861 and 2013. Different pieces of legislation provided varying levels of protection for individual species and sometimes led to confusion about which species were protected. The reasons why species were protected are explained.

Go to Legal protection of New Zealand’s indigenous terrestrial fauna – an historical review

Domestic expenditure of the Hector family in the early 1870s

Simon Nathan, Judith Nathan and Rowan Burns

Analysis of a large bundle of family accounts has yielded information on the lifestyle of James and Georgiana Hector in the early 1870s, when they lived in Museum House next door to the Colonial Museum in Wellington. James Hector was director of the Geological Survey and Colonial Museum. With a salary of £800 a year, as well as income from a marriage settlement, the Hectors were able to live well as part of the colonial social elite. Dr Hector clearly managed his money carefully, and there is no sign of high expenditure on social activities or entertaining. Mrs Hector patronised many Wellington shops, among which Kirkcaldie and Stains is the only one still in business.

Domestic expenditure of the Hector family in the early 1870s (5.40 MB)

Ko Tītokowaru: te poupou rangatira Tītokowaru: a carved panel of the Taranaki leader

Hokimate P.Harwood

In 1905, Augustus Hamilton, the director of the Colonial Museum (now the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, or Te Papa), bought for the museum a carved poupou (panel) that depicted Taranaki rangatira (chief ) Tïtokowaru, which he acquired from his friend Henry Hill, a Napier educator and collector. Around 1953, this poupou was loaned to the Department of External Affairs for display at the newly opened New Zealand Embassy in Paris, France. The poupou remained in Paris until recently, when research in 2012 revealed its whereabouts, and ensuing discussions allowed its return to Aotearoa New Zealand. This paper documents the history and initial acquisition of the Tïtokowaru poupou for the museum collections, its loan to Paris, and its subsequent return to Te Papa in October 2013.

Ko Tītokowaru: te poupou rangatira Tītokowaru: a carved panel of the Taranaki leader (4.18 MB)

Legal protection of New Zealand’s indigenous terrestrial fauna – an historical review

Colin M. Miskelly

New Zealand has had a complex history of wildlife protection, with at least 609 different pieces of legislation affecting the protection of native wildlife between 1861 and 2013. The first species to be fully protected was the tūī (Prosthemadera novaeseelandiae), which was listed as a native game species in 1873 and excluded from hunting in all game season notices continuously from 1878, until being absolutely protected in 1906. The white heron (Ardea modesta) and crested grebe (Podiceps cristatus) were similarly protected nationwide from 1888, and the huia (Heteralocha acutirostris) from 1892. Other species listed as native game before 1903 were not consistently excluded from hunting in game season notices, meaning that such iconic species as kiwi (Apteryx spp.), kākāpō (Strigopshabroptilus), kōkako (Callaeas spp.), saddlebacks (Philesturnus spp.), stitchbird (Notiomystis cincta) and bellbird (Anthornis melanura) could still be taken or killed during the game season until they were absolutely protected in 1906. The tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) was added to the native game list in 1895, but due to inadequate legislation was not absolutely protected until 1907. The Governor of the Colony of New Zealand had the power to absolutely protect native birds from 1886, but this was not used until 1903, when first the blue duck (Hymenolaimus malacorhynchus) and then the huia were given the status of absolutely protected, followed by more than 130 bird species by the end of 1906. The groundbreaking Animals Protection Act 1907 listed 23 bird species, four genera, one family (cuckoos, Cuculidae) and tuatara as protected. The Animals Protection Amendment Act 1910 extended protection to all indigenous bird species, but led to confusion as to which bird species were ‘indigenous’. This confusion was removed by the Animals Protection and Game Act 1921–22, which presented a long list of absolutely protected species. The 1921– 22 Act introduced further problems through omission of species that had not yet been discovered or named, including South Island snipe (Coenocorypha iredalei), Chatham Island mollymawk (Thalassarche eremita), Pycroft’s petrel (Pterodroma pycrofti), Archey’s frog (Leiopelma archeyi) and Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica). The Wildlife Act 1953 avoided missing unknown species by reverting to the 1910 approach of making everything protected unless listed as ‘not protected’. Further, by covering both native and introduced species, the 1953 Act was able to avoid use of ambiguous terms such as ‘indigenous’. The 1953 Act has provided a stable platform for wildlife protection for 60 years, including allowing the addition of selected threatened terrestrial invertebrates in 1980, 1986 and 2010, and all New Zealand lizards in 1981 and 1996. The reasons why species were protected are explained.

Legal protection of New Zealand’s indigenous terrestrial fauna – an historical review (2.19 MB)

You might also like

Our history

Discover how we came to be, from the opening of the Colonial Museum in 1865 to Te Papa today.